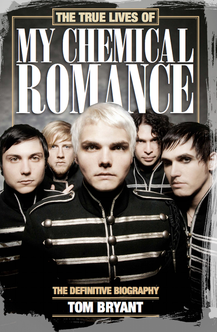

The true lives of my chemical romance: a biography

|

The definitive biography of My Chemical Romance

My Chemical Romance are the most significant band in alternative rock for the last decade, selling 5 million albums and selling out arenas worldwide until their split after twelve years together. Author Tom Bryant has been given unparalleled access to the band over the course of their extraordinary career and has a unique archive of interviews with Gerard Way and his brother Mikey, Ray Toro and Frank Iero, as well as their friends and those closest to them, allowing him to go behind the scenes and bring their stories to life. From their New Jersey beginnings to international superstardom, from the demons they have battled to the power of their lyrics and their extraordinary connection with their fans, this is the definitive biography of the most adored rock band this century, a story of self-belief and the pursuit of dreams. UK edition: http://amzn.to/1myGFjA US edition: http://amzn.to/1ig2Lo7 |

On the road with My Chemical Romance, Kerrang! November 2005

My Chemical Romance’s dressing room at the Manchester Apollo is a plush wood-lined affair, leather sofas in a square around a coffee table. Next door there’s a make-up room, a mirror lined with light-bulbs, the surfaces lined with the band’s rider.

It’s in here that My Chemical Romance are going through their pre-show routine. Ray Toro and Gerard Way are bouncing up and down, doing ‘jumping-jacks’. Meanwhile there’s banter, “dicking around,” according to Gerard, while they, “put on their war-paint”. A round of high-fives then they stride down the narrow and winding staircase that leads to the stage, the focus purely on what lies ahead.

Out front, the crowd is heaving. One fan, Nat Dean, has been waiting here with her friends since midday. It’s been a slack day for them. On virtually every other day of this tour they’ve been outside the venue at six am. “Why do we wait around that long?” she asks. “In case we get to meet them of course.”

They’re not the only ones this dedicated. Fans are pressed up to the barriers, at least ten have already been carried out – pink faced, glazed expression, eyeballs rolled back – during support band Every Time I Die’s set. This is more than just a gig to these people; this is almost a religion, a celebration of their heroes becoming the best band in the world.

Then the lights go down and The Smiths’ ‘Please Please Please, Let Me Get What I Want’ creeps out over the PA. The screams are deafening, a hysterical howl of emotion and anticipation. Backstage the adrenalin surges, brief glances are shared and each band member knows that this is what they’ve been waiting for all day, what all the hanging around, interviews, photo-sessions and travelling have been for. Tonight, as with every night, they have to play the best show of their lives.

In front of them, there’s a seething mass of people swarming over each other, clamouring for a better view, for the band’s attention, to be filled by the music. This is the story of what it looks like inside that hurricane.

IT’S BEEN a remarkable 12 months for My Chemical Romance. At the beginning of the year they were playing second fiddle to Taking Back Sunday at the Brixton Academy. By the end of it, they sold out <<two>> nights there on their own. They’ve risen from a band with potential to world-beaters. As Gerard says, “If there were two rock bands that stood out this year, it was Green Day and us.” It’s both true and staggering that a band that few had heard of a year ago could be the equals of the biggest rock band in the world.

Earlier today, as they soundcheck, what’s most evident is the hunger to get things right. They spend half an hour working on a new song, ‘Disenchanted’. They speed it up, and then slow it down; all of them listening intently to their own playing to make sure it’s perfect. Given the reaction they receive later when they play it, it wouldn’t have mattered if it was a nursery rhyme. Such is their desire to nail it onstage that they’ll still be tinkering further the next night in Dublin.

All the while, Gerard is sniffing and blowing his nose, the victim of a brutal cold that will soon take his brother Mikey Way down too. You can tell it’s getting to them, Gerard’s usual chirpiness is replaced with a scowl and, rather than the customary cigarette in his hand, he clutches a hot ginger tea to preserve his voice.

Tonight is a good gig – though perhaps not as sharp as they expected. London, according to the Gerard, “Was special. So special that it felt like we were at home.” It’s something they talk about as they come offstage for their encore. “We’re chatty as hell during the encore,” says Gerard. “It’s probably the silliest moment you’ll ever catch us. It’s the biggest release – you’re offstage, you’re all sweaty and just talking about all the stupid shit that happened onstage. You’re always apologising for making mistakes that no-one else noticed.”

Tonight they talk about Mikey Way who managed to get hit by chewing gum and slip over backwards – “It wasn’t my night,” he smiles. “Bob’s [Bryar – drums] always talking about something he fucked up that no-one heard or about his drumstick trick,” adds Ray. “We have to tell him we saw it even if we didn’t just to keep him happy. Drummers are the most sensitive people…”

It’s not a long break – they’re back out within minutes, again to rapturous screams. Two more songs and they’re done, heading back to their dressing room to collapse. “If it’s been a good night you don’t have to try to come down from the buzz of being onstage at all,” says Frank. “You’re totally spent, you have absolutely nothing left. Being completely drained means you’ve played well.”

“The show is the reason you’re there,” adds Gerard. “Afterwards we all just sit together and talk, like a bunch of little old men.”

They shower and change, waiting for the stack of pizzas they always order after the gig, before emerging along the venue’s breeze-block corridors, all with hoods on, all looking freezing. Frank, Mikey and Ray head into the catering room to play online computer games, Gerard wearily heads walks to the bus, running the gauntlet of fans between the venue and his bunk.

He spends 15 minutes there signing as much as he can before the tiredness gets to him. Around him, some scream while some look dazed in awe, all push t-shirts, posters and albums at him to sign. Some want photos, a few demanding he pull ridiculous faces for the camera – a request at which he smiles witheringly and ignores. Some pull at him, some press against the barriers. “Sometimes you feel like an object during those moments and that’s one of the biggest drags,” he says.

“You feel like you’re in a cage, that you only exist for their amusement,” adds Ray. “That’s an odd thing. People will run along the side of the bus and shout, or they’ll be yelling at you to take your hood off or make a face.”

“But you can’t be rude to them, unless they’re rude to you,” continues Gerard. “If I don’t get a good vibe from someone, then I won’t help them out. Often I won’t do the things they tell me to do because I don’t want to become a puppet.”

It’s hardest for Mikey, “I have social anxiety. I find it hard to talk to people that I don’t really know. Sometimes I feel like people think I’m a dick. When I get approached in the street I get freaked out, I get nervous.”

Despite this, they’ll always talk to their fans, these are the people that put them where they are and they know it and love them for it.

IT’LL BE a long night as the bus rolls out of Manchester towards the ferry to Dublin. Still not accustomed to the time-difference, they sit up tonight until 8.30 am in the bus’s back room. Ray is playing ‘Grand Theft Auto’ while everyone else watches. All of them are constantly within reach of their SideKicks – handheld e-mailers, tapping out messages to friends and family constantly. As they reach the ferry, neither Ray nor Frank have slept yet. They, and the rest of the band, head to the restaurant and immediately order the full English breakfast, a British ferry tradition for them. Keith Buckley from Every Time I Die joins them. “He was horrified by what we were eating,” laughs Gerard, “So we made him have one too.” It wasn’t a good decision, within minutes of leaving the port, they hit a rough sea. Bottles fall off shelves as the boat pitches and rolls, standing is impossible without clinging to the walls and both Ray and Keith Buckley are throwing up while hardened Irish drinkers look up from their early pints with amusement.

IN DUBLIN, a crowd has been forming in front of The Ambassador venue from 6am. Ali Doyle was one of the first there and despite the cold rain she can barely contain herself. “This band saved my life,” she screams. “Bands never come to Ireland so it’s amazing that they’ve have.” It’s a sentiment echoed along the ever-stretching queue. Many clutch drawings, letters, presents and flags that they heap onto anyone heading inside, anyone who might see their heroes. You get the impression they don’t see anyone in the band as a person, to some of the fans here they’re almost unreal.

“People that put us on pedestals are missing the point,” says Gerard. “I can only be myself. Some people build us up into people we’re not. Maybe people want me to be throwing chairs through windows but I try to think of ways not to be ‘Gerard Way from My Chemical Romance’. A lot of my day consists of trying to be as normal as possible. I want to do mundane things.”

It’s a sentiment close to Gerard’s heart. He’s had well-documented troubles with alcohol in the past – all behind him now. Those, he admits, were the moments when he had lost sight of who he was, when he had got sucked up into the act of playing the rock star.

“I’d lost myself so much,” he says. “I’d lost myself in a character, in the band and in booze. I never want to back there – it’s not where any of the lyrics came from and it’s not where the music we write together came from. It was just a messed up place that I was in. It was an escape and I don’t feel like escaping anymore.”

It means that a day with My Chemical Romance in a strange town <<is>> normal – well, as normal as it can be in a band. They go out and look around town, stopping in a comic store to browse the racks. They head out for a coffee every now and again because they want to remain grounded, to remain true to themselves. It’s only when they walk onstage that they want to feel any different.

“The point is to become something extraordinary for an hour a day,” says Gerard. “We’re jerk-offs and losers, like a lot of people, but for an hour a day we go onstage and we become untouchable and that’s what’s special.”

Inevitably though, there are moments when it does get on top of them, when being away from home for such long periods makes it hard to keep in touch with the world they left behind in Jersey.

“You’ll hear from someone at home and something bad has happened,” says Frank. “What are you supposed to do or say? You can be halfway round the world when something happens and it makes you feel helpless. One of my biggest fears is not being there when something terrible happens. You feel useless.”

Meanwhile rumours and stories continue to circulate around the band, stories that aren’t true and that the band have no control over. On the day of the gig in Dublin there are rumours the band have broken up and are no longer speaking to each other. They all laugh together in their backstage dressing room.

“That’s mostly our reaction because it’s so insane,” says Gerard. “But you can go from one extreme to another – if it’s really personal shit, you get pissed off. It bugs me when people think they know me and what my life is like. People make assumptions about us and that really gets to me. They don’t know what we go through; they don’t know what it’s like to be in this band. It’s amazing the lengths people will go to in order to bring you down because they’re incapable of understanding.”

BEFORE THE show tonight, the routine is the same. The door is closed to everyone but the band again as they focus on the gig and then, once again, they explode onstage. There’s a unity there, one born from fierce camaraderie. “You have to be a gang,” says Frank. “You realise it’s you versus the world and no-one else is looking out for you.”

“Yeah – but less so now,” adds Gerard. “We wouldn’t be able to play onstage if we didn’t have each other’s backs. But now it feels like we’ve won something. We used to want to prove something. We used to go onstage angry and that was to prove something to ourselves. Now we think we’ve established that we’re different and deserve to be respected for it. It’s less ‘us against the world’ now. It feels like us and our crowd against the world.”

Onstage, they claim not to think about what they’re doing. Gerard says he can’t look at the audience too much, that he can’t read banners and signs being held up because he starts reading them and forgets what he’s singing. His body is on automatic pilot – his moves natural and instinctive. “There are certain parts of certain songs that I’ll always punch my fist out to and I don’t know why,” he says.

Frank can’t look at the crowd at all. “Maybe that’s just the way I play but I can’t do it,” he says. “Unless you’ve done it, you can’t know how it feels to be up there. It’s like nothing else. I feel connected to the crowd in one way but, in another, I’m completely shut off. I’d play the same way in front of two people or a million.”

MEANWHILE, OUTSIDE the venue, those that don’t have tickets mill around. At least fifty are pressing one ear against The Ambassador’s walls, desperate to hear the gig even if they can’t see it. They’re joined by a rush of those inside as the gig finishes. Parents are searching for their children, while those same children duck out of sight and around the corner for a last cigarette.

The band sit in their dressing room, waiting for their pizzas to arrive while a representative from their Irish label marshals a gang of kids together who’ve won a competition to meet the band. Though you sense the band would prefer not to do this, they greet the prize-winners with incredible grace when they emerge. It would be hard for anyone to know how to react when strangers spout facts about your life at you, hustle to get near you and clamour for your attention but My Chemical Romance deal with it with charm despite their obvious exhaustion. Still, it’s occasionally awkward – entertaining fans face-to-face is a different matter to entertaining a faceless mass from the stage.

Then My Chemical Romance relax and know they have nothing left to do tonight. They walk back to the dressing room and that’s the last we’ll see of My Chemical Romance for a while. They’ve waved farewell to ‘Three Cheers For Sweet Revenge’, this tour a celebration of its success and a nod towards the new.

“It’s been really special,” says Gerard. “Whenever you tour, you hope it will feel like a victory lap. This tour is the first time we feel we’ve earned that. For the first time it’s felt like everyone in the crowd wants to be at our shows. No-one’s here to ridicule us, no-one wants to tell us how much we suck now, these crowds feel like they’re behind us. These crowds want to be here because they feel they’ve earned it just as much as us. That’s special.”

© Tom Bryant 2012

It’s in here that My Chemical Romance are going through their pre-show routine. Ray Toro and Gerard Way are bouncing up and down, doing ‘jumping-jacks’. Meanwhile there’s banter, “dicking around,” according to Gerard, while they, “put on their war-paint”. A round of high-fives then they stride down the narrow and winding staircase that leads to the stage, the focus purely on what lies ahead.

Out front, the crowd is heaving. One fan, Nat Dean, has been waiting here with her friends since midday. It’s been a slack day for them. On virtually every other day of this tour they’ve been outside the venue at six am. “Why do we wait around that long?” she asks. “In case we get to meet them of course.”

They’re not the only ones this dedicated. Fans are pressed up to the barriers, at least ten have already been carried out – pink faced, glazed expression, eyeballs rolled back – during support band Every Time I Die’s set. This is more than just a gig to these people; this is almost a religion, a celebration of their heroes becoming the best band in the world.

Then the lights go down and The Smiths’ ‘Please Please Please, Let Me Get What I Want’ creeps out over the PA. The screams are deafening, a hysterical howl of emotion and anticipation. Backstage the adrenalin surges, brief glances are shared and each band member knows that this is what they’ve been waiting for all day, what all the hanging around, interviews, photo-sessions and travelling have been for. Tonight, as with every night, they have to play the best show of their lives.

In front of them, there’s a seething mass of people swarming over each other, clamouring for a better view, for the band’s attention, to be filled by the music. This is the story of what it looks like inside that hurricane.

IT’S BEEN a remarkable 12 months for My Chemical Romance. At the beginning of the year they were playing second fiddle to Taking Back Sunday at the Brixton Academy. By the end of it, they sold out <<two>> nights there on their own. They’ve risen from a band with potential to world-beaters. As Gerard says, “If there were two rock bands that stood out this year, it was Green Day and us.” It’s both true and staggering that a band that few had heard of a year ago could be the equals of the biggest rock band in the world.

Earlier today, as they soundcheck, what’s most evident is the hunger to get things right. They spend half an hour working on a new song, ‘Disenchanted’. They speed it up, and then slow it down; all of them listening intently to their own playing to make sure it’s perfect. Given the reaction they receive later when they play it, it wouldn’t have mattered if it was a nursery rhyme. Such is their desire to nail it onstage that they’ll still be tinkering further the next night in Dublin.

All the while, Gerard is sniffing and blowing his nose, the victim of a brutal cold that will soon take his brother Mikey Way down too. You can tell it’s getting to them, Gerard’s usual chirpiness is replaced with a scowl and, rather than the customary cigarette in his hand, he clutches a hot ginger tea to preserve his voice.

Tonight is a good gig – though perhaps not as sharp as they expected. London, according to the Gerard, “Was special. So special that it felt like we were at home.” It’s something they talk about as they come offstage for their encore. “We’re chatty as hell during the encore,” says Gerard. “It’s probably the silliest moment you’ll ever catch us. It’s the biggest release – you’re offstage, you’re all sweaty and just talking about all the stupid shit that happened onstage. You’re always apologising for making mistakes that no-one else noticed.”

Tonight they talk about Mikey Way who managed to get hit by chewing gum and slip over backwards – “It wasn’t my night,” he smiles. “Bob’s [Bryar – drums] always talking about something he fucked up that no-one heard or about his drumstick trick,” adds Ray. “We have to tell him we saw it even if we didn’t just to keep him happy. Drummers are the most sensitive people…”

It’s not a long break – they’re back out within minutes, again to rapturous screams. Two more songs and they’re done, heading back to their dressing room to collapse. “If it’s been a good night you don’t have to try to come down from the buzz of being onstage at all,” says Frank. “You’re totally spent, you have absolutely nothing left. Being completely drained means you’ve played well.”

“The show is the reason you’re there,” adds Gerard. “Afterwards we all just sit together and talk, like a bunch of little old men.”

They shower and change, waiting for the stack of pizzas they always order after the gig, before emerging along the venue’s breeze-block corridors, all with hoods on, all looking freezing. Frank, Mikey and Ray head into the catering room to play online computer games, Gerard wearily heads walks to the bus, running the gauntlet of fans between the venue and his bunk.

He spends 15 minutes there signing as much as he can before the tiredness gets to him. Around him, some scream while some look dazed in awe, all push t-shirts, posters and albums at him to sign. Some want photos, a few demanding he pull ridiculous faces for the camera – a request at which he smiles witheringly and ignores. Some pull at him, some press against the barriers. “Sometimes you feel like an object during those moments and that’s one of the biggest drags,” he says.

“You feel like you’re in a cage, that you only exist for their amusement,” adds Ray. “That’s an odd thing. People will run along the side of the bus and shout, or they’ll be yelling at you to take your hood off or make a face.”

“But you can’t be rude to them, unless they’re rude to you,” continues Gerard. “If I don’t get a good vibe from someone, then I won’t help them out. Often I won’t do the things they tell me to do because I don’t want to become a puppet.”

It’s hardest for Mikey, “I have social anxiety. I find it hard to talk to people that I don’t really know. Sometimes I feel like people think I’m a dick. When I get approached in the street I get freaked out, I get nervous.”

Despite this, they’ll always talk to their fans, these are the people that put them where they are and they know it and love them for it.

IT’LL BE a long night as the bus rolls out of Manchester towards the ferry to Dublin. Still not accustomed to the time-difference, they sit up tonight until 8.30 am in the bus’s back room. Ray is playing ‘Grand Theft Auto’ while everyone else watches. All of them are constantly within reach of their SideKicks – handheld e-mailers, tapping out messages to friends and family constantly. As they reach the ferry, neither Ray nor Frank have slept yet. They, and the rest of the band, head to the restaurant and immediately order the full English breakfast, a British ferry tradition for them. Keith Buckley from Every Time I Die joins them. “He was horrified by what we were eating,” laughs Gerard, “So we made him have one too.” It wasn’t a good decision, within minutes of leaving the port, they hit a rough sea. Bottles fall off shelves as the boat pitches and rolls, standing is impossible without clinging to the walls and both Ray and Keith Buckley are throwing up while hardened Irish drinkers look up from their early pints with amusement.

IN DUBLIN, a crowd has been forming in front of The Ambassador venue from 6am. Ali Doyle was one of the first there and despite the cold rain she can barely contain herself. “This band saved my life,” she screams. “Bands never come to Ireland so it’s amazing that they’ve have.” It’s a sentiment echoed along the ever-stretching queue. Many clutch drawings, letters, presents and flags that they heap onto anyone heading inside, anyone who might see their heroes. You get the impression they don’t see anyone in the band as a person, to some of the fans here they’re almost unreal.

“People that put us on pedestals are missing the point,” says Gerard. “I can only be myself. Some people build us up into people we’re not. Maybe people want me to be throwing chairs through windows but I try to think of ways not to be ‘Gerard Way from My Chemical Romance’. A lot of my day consists of trying to be as normal as possible. I want to do mundane things.”

It’s a sentiment close to Gerard’s heart. He’s had well-documented troubles with alcohol in the past – all behind him now. Those, he admits, were the moments when he had lost sight of who he was, when he had got sucked up into the act of playing the rock star.

“I’d lost myself so much,” he says. “I’d lost myself in a character, in the band and in booze. I never want to back there – it’s not where any of the lyrics came from and it’s not where the music we write together came from. It was just a messed up place that I was in. It was an escape and I don’t feel like escaping anymore.”

It means that a day with My Chemical Romance in a strange town <<is>> normal – well, as normal as it can be in a band. They go out and look around town, stopping in a comic store to browse the racks. They head out for a coffee every now and again because they want to remain grounded, to remain true to themselves. It’s only when they walk onstage that they want to feel any different.

“The point is to become something extraordinary for an hour a day,” says Gerard. “We’re jerk-offs and losers, like a lot of people, but for an hour a day we go onstage and we become untouchable and that’s what’s special.”

Inevitably though, there are moments when it does get on top of them, when being away from home for such long periods makes it hard to keep in touch with the world they left behind in Jersey.

“You’ll hear from someone at home and something bad has happened,” says Frank. “What are you supposed to do or say? You can be halfway round the world when something happens and it makes you feel helpless. One of my biggest fears is not being there when something terrible happens. You feel useless.”

Meanwhile rumours and stories continue to circulate around the band, stories that aren’t true and that the band have no control over. On the day of the gig in Dublin there are rumours the band have broken up and are no longer speaking to each other. They all laugh together in their backstage dressing room.

“That’s mostly our reaction because it’s so insane,” says Gerard. “But you can go from one extreme to another – if it’s really personal shit, you get pissed off. It bugs me when people think they know me and what my life is like. People make assumptions about us and that really gets to me. They don’t know what we go through; they don’t know what it’s like to be in this band. It’s amazing the lengths people will go to in order to bring you down because they’re incapable of understanding.”

BEFORE THE show tonight, the routine is the same. The door is closed to everyone but the band again as they focus on the gig and then, once again, they explode onstage. There’s a unity there, one born from fierce camaraderie. “You have to be a gang,” says Frank. “You realise it’s you versus the world and no-one else is looking out for you.”

“Yeah – but less so now,” adds Gerard. “We wouldn’t be able to play onstage if we didn’t have each other’s backs. But now it feels like we’ve won something. We used to want to prove something. We used to go onstage angry and that was to prove something to ourselves. Now we think we’ve established that we’re different and deserve to be respected for it. It’s less ‘us against the world’ now. It feels like us and our crowd against the world.”

Onstage, they claim not to think about what they’re doing. Gerard says he can’t look at the audience too much, that he can’t read banners and signs being held up because he starts reading them and forgets what he’s singing. His body is on automatic pilot – his moves natural and instinctive. “There are certain parts of certain songs that I’ll always punch my fist out to and I don’t know why,” he says.

Frank can’t look at the crowd at all. “Maybe that’s just the way I play but I can’t do it,” he says. “Unless you’ve done it, you can’t know how it feels to be up there. It’s like nothing else. I feel connected to the crowd in one way but, in another, I’m completely shut off. I’d play the same way in front of two people or a million.”

MEANWHILE, OUTSIDE the venue, those that don’t have tickets mill around. At least fifty are pressing one ear against The Ambassador’s walls, desperate to hear the gig even if they can’t see it. They’re joined by a rush of those inside as the gig finishes. Parents are searching for their children, while those same children duck out of sight and around the corner for a last cigarette.

The band sit in their dressing room, waiting for their pizzas to arrive while a representative from their Irish label marshals a gang of kids together who’ve won a competition to meet the band. Though you sense the band would prefer not to do this, they greet the prize-winners with incredible grace when they emerge. It would be hard for anyone to know how to react when strangers spout facts about your life at you, hustle to get near you and clamour for your attention but My Chemical Romance deal with it with charm despite their obvious exhaustion. Still, it’s occasionally awkward – entertaining fans face-to-face is a different matter to entertaining a faceless mass from the stage.

Then My Chemical Romance relax and know they have nothing left to do tonight. They walk back to the dressing room and that’s the last we’ll see of My Chemical Romance for a while. They’ve waved farewell to ‘Three Cheers For Sweet Revenge’, this tour a celebration of its success and a nod towards the new.

“It’s been really special,” says Gerard. “Whenever you tour, you hope it will feel like a victory lap. This tour is the first time we feel we’ve earned that. For the first time it’s felt like everyone in the crowd wants to be at our shows. No-one’s here to ridicule us, no-one wants to tell us how much we suck now, these crowds feel like they’re behind us. These crowds want to be here because they feel they’ve earned it just as much as us. That’s special.”

© Tom Bryant 2012