The true lives of my chemical romance: a biography

|

The definitive biography of My Chemical Romance

My Chemical Romance are the most significant band in alternative rock for the last decade, selling 5 million albums and selling out arenas worldwide until their split after twelve years together. Author Tom Bryant has been given unparalleled access to the band over the course of their extraordinary career and has a unique archive of interviews with Gerard Way and his brother Mikey, Ray Toro and Frank Iero, as well as their friends and those closest to them, allowing him to go behind the scenes and bring their stories to life. From their New Jersey beginnings to international superstardom, from the demons they have battled to the power of their lyrics and their extraordinary connection with their fans, this is the definitive biography of the most adored rock band this century, a story of self-belief and the pursuit of dreams. UK edition: http://amzn.to/1myGFjA US edition: http://amzn.to/1ig2Lo7 |

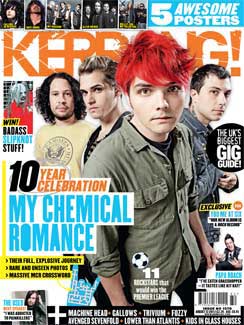

My Chemical Romance: A 10 Year Celebration, Kerrang! August 13, 2011

THE FOUR members of My Chemical Romance are sitting around a table in the open-air restaurant of a Lisbon hotel. Beyond is a view of the Bairro Alto, while the piercing blue of Portuguese sky is dotted with high clouds.

But the topic of conversation isn’t about how pleasant it is here; in fact it’s about how peculiar it seems that the songs they wrote as nobodies in a New Jersey basement in 2001 have, 10 years later, led them here. As singer Gerard Way, his brother and bassist Mikey and guitarists Frank Iero and Ray Toro weave their way through their past, they laugh a lot as they remember old times and old friends from the past.

But there are times, too, that they’re sombre. Because despite their success, My Chemical Romance’s story is not always celebratory. There have been drug and drink addictions, there have been breakdowns and moments they feared they were losing their minds.

Touchingly, as they talk, there are even apologies as one member realises what he put another through. And there are revelations too, moments of genuine shock as facts eek out that others were unaware of. Because today, they are in the mood to lay out their secret history.

Finally, after they’ve talked of the rawness of their early years, told the story of how Three Cheers For Sweet Revenge made them stars, then detailed the triumph and madness of The Black Parade, Gerard leans back for a minute.

He’s thinking about their very first show in a VFW Hall in Ewing, New Jersey, in October 2001. Back then, their drummer was an old friend called Matt ‘Otter’ Pelissier; Frank, just a friend rather than a member then, was in the headline band, Pencey Prep. And briefly, Gerard is back amidst the sweat, the energy and the rawness of that gig.

Then he says: “Looking out over Lisbon, it’s surreal to look back to those basement shows. The songs we wrote thousands of literal and metaphorical miles away, are what started us on the road here. It’s very strange, but very cool.”

This, then, is that journey.

What was that first show like?

Frank: “They were drunk. Everyone was really nervous and so we all went out to the Pencey van and drank.”

Mikey: “I drank seven beers in five minutes. I was so petrified.”

Frank: “When they finally got onstage it was like watching a hurricane. The place went crazy. Ray and Gerard were kicking each other, it was awesome. You just knew something important was happening. From the first note they played, they were my favourite band.”

Mikey: “We opened with Skylines And Turnstiles and I didn’t look up until we were halfway through. Then I went, ‘Holy crap!’ The kids at the front were… well, I don’t know what they were doing. I guess they were dancing. Whatever it was, they were excited.”

Ray: “I’m a quiet dude but that music made me want to let everything out. My Chem felt different: we were making music I had never heard before. There was this kinetic energy.”

Gerard: “Afterwards, I felt like I had been in a car accident – but a really great one. It was real magical. We couldn’t play the songs without getting intense: we’d soundcheck and injure ourselves. We had to get by on the performance and the music; we had nothing else.”

Why did you ask Frank to join?

Gerard: “When we watched Pencey Prep onstage, it was obvious what we were missing. We already had some dynamite but we needed more. Frank was the extra dynamite.”

Frank: “I was hanging out while they recorded a demo of Vampires Will Never Hurt You and I got really, really high. Ray had laid down 14 guitar parts and somebody said, ‘If you add another guitarist, you could play this live’. Someone replied, ‘The only guy we’ve considered is too high to get off the couch’. That was the first time I thought I might play in my favourite band – it scared the shit out of me.”

Gerard drew comics and wrote short stories but few had seen them. Was recording your debut finally a chance to be heard?

Gerard: “It was. I had all these weird notebooks full of writing about how disassociated I felt in my early 20s. I was really dissatisfied with where I – and everyone I knew – was destined to end up. We were all going to end up as nothing. That’s what the band was born out of.”

It was released in July 2002, what do you think of it now?

Ray: “You can hear the nervousness and excitement. Every song speeds up which gives them a lot of character. I like the rawness, especially in the vocals. It sounds very true. I get emotional too. Early Sunsets Over Monroeville is unlike anything we’ve ever done since – it’s amazing.”

Did you have any goals after its release?

Frank: “We only really had one – to get as far from home as possible. We just wanted to play. We’d play anywhere and with anyone and we’d destroy shit.”

Mikey: “If we could afford it, we’d crash in cheap hotels. We’d send one person in to get the room, then we’d all sneak in when no-one was looking. All five of us would share the same bed.”

Gerard: “We played with Christian bands, metal bands, hardcore bands, indie bands, anyone. Only five or 10 people were there to see us, but they were our people. And they’d be noisy, too. I once watched someone clock a kid who’d been having a go at us in the face. It was awesome.”

But as you toured, Gerard and Mikey began to drink.

Gerard: “Alcohol was a coping tool. There were just so many hours to kill. And the music was so intense; it was about a lot of dark, fucked up things and I had to live through them every time we played. That’s why I was drinking.”

Mikey: “I missed home and I was nervous to get onstage. It was a means to an end, I don’t remember enjoying it.”

BY NOVEMBER 2003, life was looking good for My Chemical Romance. They had signed a major label deal and touring in both Europe and America had built them a small but loyal fanbase. They had been thinking about their second album, Three Cheers For Sweet Revenge, too. “We decided,” says Ray, “that nothing should be taboo. If a song was great then we had to do it, whether it fitted or not.”

In Los Angeles’ Bay 7 Studios, producer Howard Benson pushed them hard. He hadn’t been impressed with their demo but, in Gerard, recognised something. “I always look for a star in a band,” he has said, “and Gerard is certainly that.” So he forced him to access his emotions and urged him to assume different identities for each song. “I remember Howard encouraging me to get pretty weird,” Gerard has said.

But throughout the sessions, there was something affecting the Way brothers. A month earlier, their grandmother – the driving influence in steering them towards music – died. Gerard poured his feelings into the album and particularly the song Helena, named after her. He has said in the past that, “All the fucking anger, the spite, the beef with God, the angst, aggression and the fucking venom – every emotion you go through when you’re grieving – is on Revenge.”

And he took those emotions and added them to a cocktail of alcohol, Xanax, pills and cocaine.

How much did the death of your grandmother affect the record?

Gerard: “After our grandmother died, getting back to music was the only place that made us feel good. But that’s also when the drug and alcohol thing developed into a problem. I definitely allowed that to flourish in LA.”

It got pretty wild for all of you. Frank has said he’d go out on a Friday night, take pills, and wake up on Monday with no memory of the weekend.

Frank: “Yeah, that was weird. I’d wake up and not know what day it was.”

Gerard: “That was the same for a few of us. When we weren’t making music, there was such a fog. Some of us were experimenting with pills. We’d all just vanish for days when we weren’t in the studio.”

Ray: “Really? I had no idea any of that stuff was going on. I was so naïve. I knew there were a couple of instances because I had a talk with Gerard after one, but I didn’t see anything <<that>> different. I’m actually kind of surprised; I didn’t know any of this until today. Frank was taking pills? This is a revelation to me.”

Did it affect the album?

Gerard: “I couldn’t sing one morning as I had done cocaine all night. I felt awful, so I told Ray and we had a serious talk. It wasn’t a problem again until we were on the road.”

IN KANSAS, in July 2004 a month after the record was released, the problem reared its head. After combining an eight-ball of cocaine with pills and his daily bottle of vodka, he had a breakdown. “I had done a lot of cocaine,” he says, “And I just crashed.”

But, with Revenge just released, there were a list of dates in Japan to complete. There, Gerard lost his mind, embarking on self-destructive sake binges until he staggered offstage after their final show and collapsed in a puddle of his own vomit. Deeply worried, Ray said simply: “You need help.”

As they flew home, they knew there were other problems too: it was felt drummer Matt Pelissier was no longer right for the band. So, as Gerard spoke to a psychiatrist and got sober, Pelissier was replaced with old friend Bob Bryar. Then My Chemical Romance decided it was about time they got serious.

“We came up with a battle-plan,” says Frank. “We didn’t want the band to end, so we had to fix it. So everyone got to work. The record had barely come out and we were very proud of it. To call it quits at that point wasn’t an option.”

So they did what they had done at the start: they toured.

“From that moment on, there was no looking back,” says Gerard. “We worked hard and we worked constantly. Everything got serious and fucking dedicated.”

And by the time it came to make their next record, their work ethic had made them huge. As The Black Parade loomed, they had gone from nobodies with guitars to rock stars. But, as they were finding out, the subsequent attention, scrutiny, criticism and praise had its own problems.

When, in April 2006, they flew to Los Angeles to record – this time in the remote and, the band claim, haunted Paramour Mansion with Green Day producer Rob Cavallo – those pressures had reached boiling point. Mikey, for one, was so plagued, he temporarily left the band to seek help for his depression, alcohol and drug problems. Meanwhile, the rest of My Chemical Romance weren’t too far off madness themselves.

What are your memories going into Parade?

Gerard: “The band had got really big and so there was a lot of pressure. A lot of people thought we’d be a flash in the pan. That was hard for us. There were all these expectations about what we’d do, so we did the opposite. We made a batshit crazy album.”

The strain of making it forced Mikey to leave and seek therapy.

Mikey: “I was 23, 24 and I was drinking at the time. I had reached an age where a lot of emotions and hormones affect you. I was at odds with myself. The band had engulfed all of us and I found it overwhelming. Recording Black Parade was the moment it all came to a head, I couldn’t stop it. I had to go away and fix myself. There were some screws loose upstairs that needed tightening.”

Gerard: “I don’t think you had screws loose, Mikey. You were processing everything that happened to us.”

Ray: “I’ve never had the chance to say this properly, so I’d like to say it now: I’m sorry Mikey. I know I contributed to what you went through. I think I lost my mind. The pressure made me think we had to be perfect all of the time. But I confused perfect playing with great playing. I’m sorry for creating that atmosphere.”

Mikey: “You don’t need to apologise Ray.”

It sounds as if the album was made under intense conditions.

Ray: “It was unhealthy. We went into it with the best intentions; in my case, those intentions expressed themselves in the wrong way. We set aside a room to have these super heavy talks and that atmosphere ran through the recording. It was a tough time. We all lost our heads.”

Gerard: “Ray was a perfectionist and I was a fucking lunatic. I was trying to oversee everything. I’d be changing things constantly: a song would start one way then, the next day, I’d force everyone to change it. We went fucking crazy. I got obsessed with death. For days, I played Passion Of The Christ with the sound off. I couldn’t get things grim enough. I ended a relationship – in fact I was so obsessed that my entire personal life got destroyed.”

Mikey: “We all became dark, morbid people. We were festering.”

Ray: “I learned so much about what not to do on that record. You can be intense in such a way that you inspire people, or you can do it in a way that you intimidate people. On Black Parade, I did it the wrong way.”

What did you think people would make of Black Parade?

Frank: “We were expecting everyone to hate it because of the success of Revenge. We were waiting for it to be torn to pieces. But, at first, there was no real good or bad reaction. People just looked at us weird, so we went on tour. It was after a year, though, that that it started to get big – so we had to keep going even though we were tired. It was crazy, we couldn’t say no to anything. We felt we owed that to the album.”

The lengthy Black Parade tour was marked by illness, burn-out and injuries. How did that feel?

Mikey: “There were times we didn’t know what country we were in, we didn’t know anything. Someone would point us at the stage and we’d head in that direction.”

Frank: “We didn’t really argue…”

Gerard: “…But we didn’t talk much either. We were quiet. We had our headphones on a lot.”

Not much fun.

Gerard: “No, not much fun.”

Frank: “That was the problem, in fact. We weren’t having fun. We started to forget we were people.”

Gerard: “By the end, we’d see ourselves in a magazine and think, ‘Again?’ If <<we>> felt like that, God knows what everyone else thought. People must have been sick of us.”

WHEN THE tour finally finished at Madison Square Gardens in May 2008, 19 months after My Chemical Romance first went on the road, they were ready to break-up. Exhausted, they had been accused of leading a suicide death cult by the Daily Mail; they had been praised, pilloried and driven to the edge of their stamina. But they had also become one of the biggest rock bands in the world; their journey from Jersey basements to worldwide arenas had been spectacular. Perhaps, then, this was a good point to call it a day.

“After Black Parade, being in the band felt like work,” says Ray. “All we wanted to do was play songs but all the other shit we had to do became the focus of the day. We wanted to start a band no-one fucking knew about again; that way we could play music without all the other shit.”

In the end, Frank did. His method of decompressing was to form the hardcore band Leathermouth and go back out on the road. The rest of the band opted to hibernate.

“I got used to not being in this thing and I liked it,” says Gerard. “I actually enjoyed not being involved.”

He married and became a father, as did Frank, but increasingly external pressure was mounting on them to record again.

“I had been a dad for two weeks when we went into the studio,” says Gerard. “I was like, ‘Let’s get this album over with. Let’s pop it out real quick’. It felt like everyone wanted us to make another record but they didn’t care what we had to say.”

They very nearly released the album they made, too. But, even after it had been played to the record company, to journalists and to friends, they scrapped it. It didn’t, as Gerard explained later, “have that greatness”. There was another issue too – drummer Bob Bryar was asked to leave the band – their only explanation is that, “it just needed to happen”.

Then, last year, they returned to the studio, with Cavallo again, to record Danger Days: The True Lives Of The Fabulous Killjoys, a record of such full-throttle, diesel-soaked, apocalyptic party music, that it met with sensational critical reviews. Daubed in bright, brash colours, finally My Chemical Romance were back.

WHICH BRINGS us back to the rooftop restaurant of this Lisbon hotel. The four of them are still chatting away, still thinking about the old days and their journey here. Ten years after they formed, there’s such shared history between them, so many interlinked memories, that they frequently finish each other’s sentence. Before they drift off, though, Ray has a final word to say about the relationship between them.

“It’s insane what we’ve been through,” he says. “Thinking back to Frank being stoned on that sofa seems a lifetime ago. And you know what? The four of us are tighter than we’ve ever been.”

*PANEL*

How to take a Reading bottling: MCR revisit their 2006 siege.

Gerard: “People were as shocked as we were that we were playing <<after>> Slayer – they’re a legendary band. The aggression started from a small group in the crowd then, unfortunately, I told people to throw stuff at us. That was a very large mistake.”

Ray: “They threw everything at us: golf balls, bottles of piss, everything.”

Frank: “What does it feel like to get hit? It fucking hurts.”

Gerard: “My worst moment was when, at the end of one song, I crawled back to the microphone. As I got there, I slipped on a peach and broke my ass.”

Mikey: “In the end, though, we saw it through. Eventually, it felt like a victory.”

© Tom Bryant 2011

But the topic of conversation isn’t about how pleasant it is here; in fact it’s about how peculiar it seems that the songs they wrote as nobodies in a New Jersey basement in 2001 have, 10 years later, led them here. As singer Gerard Way, his brother and bassist Mikey and guitarists Frank Iero and Ray Toro weave their way through their past, they laugh a lot as they remember old times and old friends from the past.

But there are times, too, that they’re sombre. Because despite their success, My Chemical Romance’s story is not always celebratory. There have been drug and drink addictions, there have been breakdowns and moments they feared they were losing their minds.

Touchingly, as they talk, there are even apologies as one member realises what he put another through. And there are revelations too, moments of genuine shock as facts eek out that others were unaware of. Because today, they are in the mood to lay out their secret history.

Finally, after they’ve talked of the rawness of their early years, told the story of how Three Cheers For Sweet Revenge made them stars, then detailed the triumph and madness of The Black Parade, Gerard leans back for a minute.

He’s thinking about their very first show in a VFW Hall in Ewing, New Jersey, in October 2001. Back then, their drummer was an old friend called Matt ‘Otter’ Pelissier; Frank, just a friend rather than a member then, was in the headline band, Pencey Prep. And briefly, Gerard is back amidst the sweat, the energy and the rawness of that gig.

Then he says: “Looking out over Lisbon, it’s surreal to look back to those basement shows. The songs we wrote thousands of literal and metaphorical miles away, are what started us on the road here. It’s very strange, but very cool.”

This, then, is that journey.

What was that first show like?

Frank: “They were drunk. Everyone was really nervous and so we all went out to the Pencey van and drank.”

Mikey: “I drank seven beers in five minutes. I was so petrified.”

Frank: “When they finally got onstage it was like watching a hurricane. The place went crazy. Ray and Gerard were kicking each other, it was awesome. You just knew something important was happening. From the first note they played, they were my favourite band.”

Mikey: “We opened with Skylines And Turnstiles and I didn’t look up until we were halfway through. Then I went, ‘Holy crap!’ The kids at the front were… well, I don’t know what they were doing. I guess they were dancing. Whatever it was, they were excited.”

Ray: “I’m a quiet dude but that music made me want to let everything out. My Chem felt different: we were making music I had never heard before. There was this kinetic energy.”

Gerard: “Afterwards, I felt like I had been in a car accident – but a really great one. It was real magical. We couldn’t play the songs without getting intense: we’d soundcheck and injure ourselves. We had to get by on the performance and the music; we had nothing else.”

Why did you ask Frank to join?

Gerard: “When we watched Pencey Prep onstage, it was obvious what we were missing. We already had some dynamite but we needed more. Frank was the extra dynamite.”

Frank: “I was hanging out while they recorded a demo of Vampires Will Never Hurt You and I got really, really high. Ray had laid down 14 guitar parts and somebody said, ‘If you add another guitarist, you could play this live’. Someone replied, ‘The only guy we’ve considered is too high to get off the couch’. That was the first time I thought I might play in my favourite band – it scared the shit out of me.”

Gerard drew comics and wrote short stories but few had seen them. Was recording your debut finally a chance to be heard?

Gerard: “It was. I had all these weird notebooks full of writing about how disassociated I felt in my early 20s. I was really dissatisfied with where I – and everyone I knew – was destined to end up. We were all going to end up as nothing. That’s what the band was born out of.”

It was released in July 2002, what do you think of it now?

Ray: “You can hear the nervousness and excitement. Every song speeds up which gives them a lot of character. I like the rawness, especially in the vocals. It sounds very true. I get emotional too. Early Sunsets Over Monroeville is unlike anything we’ve ever done since – it’s amazing.”

Did you have any goals after its release?

Frank: “We only really had one – to get as far from home as possible. We just wanted to play. We’d play anywhere and with anyone and we’d destroy shit.”

Mikey: “If we could afford it, we’d crash in cheap hotels. We’d send one person in to get the room, then we’d all sneak in when no-one was looking. All five of us would share the same bed.”

Gerard: “We played with Christian bands, metal bands, hardcore bands, indie bands, anyone. Only five or 10 people were there to see us, but they were our people. And they’d be noisy, too. I once watched someone clock a kid who’d been having a go at us in the face. It was awesome.”

But as you toured, Gerard and Mikey began to drink.

Gerard: “Alcohol was a coping tool. There were just so many hours to kill. And the music was so intense; it was about a lot of dark, fucked up things and I had to live through them every time we played. That’s why I was drinking.”

Mikey: “I missed home and I was nervous to get onstage. It was a means to an end, I don’t remember enjoying it.”

BY NOVEMBER 2003, life was looking good for My Chemical Romance. They had signed a major label deal and touring in both Europe and America had built them a small but loyal fanbase. They had been thinking about their second album, Three Cheers For Sweet Revenge, too. “We decided,” says Ray, “that nothing should be taboo. If a song was great then we had to do it, whether it fitted or not.”

In Los Angeles’ Bay 7 Studios, producer Howard Benson pushed them hard. He hadn’t been impressed with their demo but, in Gerard, recognised something. “I always look for a star in a band,” he has said, “and Gerard is certainly that.” So he forced him to access his emotions and urged him to assume different identities for each song. “I remember Howard encouraging me to get pretty weird,” Gerard has said.

But throughout the sessions, there was something affecting the Way brothers. A month earlier, their grandmother – the driving influence in steering them towards music – died. Gerard poured his feelings into the album and particularly the song Helena, named after her. He has said in the past that, “All the fucking anger, the spite, the beef with God, the angst, aggression and the fucking venom – every emotion you go through when you’re grieving – is on Revenge.”

And he took those emotions and added them to a cocktail of alcohol, Xanax, pills and cocaine.

How much did the death of your grandmother affect the record?

Gerard: “After our grandmother died, getting back to music was the only place that made us feel good. But that’s also when the drug and alcohol thing developed into a problem. I definitely allowed that to flourish in LA.”

It got pretty wild for all of you. Frank has said he’d go out on a Friday night, take pills, and wake up on Monday with no memory of the weekend.

Frank: “Yeah, that was weird. I’d wake up and not know what day it was.”

Gerard: “That was the same for a few of us. When we weren’t making music, there was such a fog. Some of us were experimenting with pills. We’d all just vanish for days when we weren’t in the studio.”

Ray: “Really? I had no idea any of that stuff was going on. I was so naïve. I knew there were a couple of instances because I had a talk with Gerard after one, but I didn’t see anything <<that>> different. I’m actually kind of surprised; I didn’t know any of this until today. Frank was taking pills? This is a revelation to me.”

Did it affect the album?

Gerard: “I couldn’t sing one morning as I had done cocaine all night. I felt awful, so I told Ray and we had a serious talk. It wasn’t a problem again until we were on the road.”

IN KANSAS, in July 2004 a month after the record was released, the problem reared its head. After combining an eight-ball of cocaine with pills and his daily bottle of vodka, he had a breakdown. “I had done a lot of cocaine,” he says, “And I just crashed.”

But, with Revenge just released, there were a list of dates in Japan to complete. There, Gerard lost his mind, embarking on self-destructive sake binges until he staggered offstage after their final show and collapsed in a puddle of his own vomit. Deeply worried, Ray said simply: “You need help.”

As they flew home, they knew there were other problems too: it was felt drummer Matt Pelissier was no longer right for the band. So, as Gerard spoke to a psychiatrist and got sober, Pelissier was replaced with old friend Bob Bryar. Then My Chemical Romance decided it was about time they got serious.

“We came up with a battle-plan,” says Frank. “We didn’t want the band to end, so we had to fix it. So everyone got to work. The record had barely come out and we were very proud of it. To call it quits at that point wasn’t an option.”

So they did what they had done at the start: they toured.

“From that moment on, there was no looking back,” says Gerard. “We worked hard and we worked constantly. Everything got serious and fucking dedicated.”

And by the time it came to make their next record, their work ethic had made them huge. As The Black Parade loomed, they had gone from nobodies with guitars to rock stars. But, as they were finding out, the subsequent attention, scrutiny, criticism and praise had its own problems.

When, in April 2006, they flew to Los Angeles to record – this time in the remote and, the band claim, haunted Paramour Mansion with Green Day producer Rob Cavallo – those pressures had reached boiling point. Mikey, for one, was so plagued, he temporarily left the band to seek help for his depression, alcohol and drug problems. Meanwhile, the rest of My Chemical Romance weren’t too far off madness themselves.

What are your memories going into Parade?

Gerard: “The band had got really big and so there was a lot of pressure. A lot of people thought we’d be a flash in the pan. That was hard for us. There were all these expectations about what we’d do, so we did the opposite. We made a batshit crazy album.”

The strain of making it forced Mikey to leave and seek therapy.

Mikey: “I was 23, 24 and I was drinking at the time. I had reached an age where a lot of emotions and hormones affect you. I was at odds with myself. The band had engulfed all of us and I found it overwhelming. Recording Black Parade was the moment it all came to a head, I couldn’t stop it. I had to go away and fix myself. There were some screws loose upstairs that needed tightening.”

Gerard: “I don’t think you had screws loose, Mikey. You were processing everything that happened to us.”

Ray: “I’ve never had the chance to say this properly, so I’d like to say it now: I’m sorry Mikey. I know I contributed to what you went through. I think I lost my mind. The pressure made me think we had to be perfect all of the time. But I confused perfect playing with great playing. I’m sorry for creating that atmosphere.”

Mikey: “You don’t need to apologise Ray.”

It sounds as if the album was made under intense conditions.

Ray: “It was unhealthy. We went into it with the best intentions; in my case, those intentions expressed themselves in the wrong way. We set aside a room to have these super heavy talks and that atmosphere ran through the recording. It was a tough time. We all lost our heads.”

Gerard: “Ray was a perfectionist and I was a fucking lunatic. I was trying to oversee everything. I’d be changing things constantly: a song would start one way then, the next day, I’d force everyone to change it. We went fucking crazy. I got obsessed with death. For days, I played Passion Of The Christ with the sound off. I couldn’t get things grim enough. I ended a relationship – in fact I was so obsessed that my entire personal life got destroyed.”

Mikey: “We all became dark, morbid people. We were festering.”

Ray: “I learned so much about what not to do on that record. You can be intense in such a way that you inspire people, or you can do it in a way that you intimidate people. On Black Parade, I did it the wrong way.”

What did you think people would make of Black Parade?

Frank: “We were expecting everyone to hate it because of the success of Revenge. We were waiting for it to be torn to pieces. But, at first, there was no real good or bad reaction. People just looked at us weird, so we went on tour. It was after a year, though, that that it started to get big – so we had to keep going even though we were tired. It was crazy, we couldn’t say no to anything. We felt we owed that to the album.”

The lengthy Black Parade tour was marked by illness, burn-out and injuries. How did that feel?

Mikey: “There were times we didn’t know what country we were in, we didn’t know anything. Someone would point us at the stage and we’d head in that direction.”

Frank: “We didn’t really argue…”

Gerard: “…But we didn’t talk much either. We were quiet. We had our headphones on a lot.”

Not much fun.

Gerard: “No, not much fun.”

Frank: “That was the problem, in fact. We weren’t having fun. We started to forget we were people.”

Gerard: “By the end, we’d see ourselves in a magazine and think, ‘Again?’ If <<we>> felt like that, God knows what everyone else thought. People must have been sick of us.”

WHEN THE tour finally finished at Madison Square Gardens in May 2008, 19 months after My Chemical Romance first went on the road, they were ready to break-up. Exhausted, they had been accused of leading a suicide death cult by the Daily Mail; they had been praised, pilloried and driven to the edge of their stamina. But they had also become one of the biggest rock bands in the world; their journey from Jersey basements to worldwide arenas had been spectacular. Perhaps, then, this was a good point to call it a day.

“After Black Parade, being in the band felt like work,” says Ray. “All we wanted to do was play songs but all the other shit we had to do became the focus of the day. We wanted to start a band no-one fucking knew about again; that way we could play music without all the other shit.”

In the end, Frank did. His method of decompressing was to form the hardcore band Leathermouth and go back out on the road. The rest of the band opted to hibernate.

“I got used to not being in this thing and I liked it,” says Gerard. “I actually enjoyed not being involved.”

He married and became a father, as did Frank, but increasingly external pressure was mounting on them to record again.

“I had been a dad for two weeks when we went into the studio,” says Gerard. “I was like, ‘Let’s get this album over with. Let’s pop it out real quick’. It felt like everyone wanted us to make another record but they didn’t care what we had to say.”

They very nearly released the album they made, too. But, even after it had been played to the record company, to journalists and to friends, they scrapped it. It didn’t, as Gerard explained later, “have that greatness”. There was another issue too – drummer Bob Bryar was asked to leave the band – their only explanation is that, “it just needed to happen”.

Then, last year, they returned to the studio, with Cavallo again, to record Danger Days: The True Lives Of The Fabulous Killjoys, a record of such full-throttle, diesel-soaked, apocalyptic party music, that it met with sensational critical reviews. Daubed in bright, brash colours, finally My Chemical Romance were back.

WHICH BRINGS us back to the rooftop restaurant of this Lisbon hotel. The four of them are still chatting away, still thinking about the old days and their journey here. Ten years after they formed, there’s such shared history between them, so many interlinked memories, that they frequently finish each other’s sentence. Before they drift off, though, Ray has a final word to say about the relationship between them.

“It’s insane what we’ve been through,” he says. “Thinking back to Frank being stoned on that sofa seems a lifetime ago. And you know what? The four of us are tighter than we’ve ever been.”

*PANEL*

How to take a Reading bottling: MCR revisit their 2006 siege.

Gerard: “People were as shocked as we were that we were playing <<after>> Slayer – they’re a legendary band. The aggression started from a small group in the crowd then, unfortunately, I told people to throw stuff at us. That was a very large mistake.”

Ray: “They threw everything at us: golf balls, bottles of piss, everything.”

Frank: “What does it feel like to get hit? It fucking hurts.”

Gerard: “My worst moment was when, at the end of one song, I crawled back to the microphone. As I got there, I slipped on a peach and broke my ass.”

Mikey: “In the end, though, we saw it through. Eventually, it felt like a victory.”

© Tom Bryant 2011