The true lives of my chemical romance: a biography

|

The definitive biography of My Chemical Romance

My Chemical Romance are the most significant band in alternative rock for the last decade, selling 5 million albums and selling out arenas worldwide until their split after twelve years together. Author Tom Bryant has been given unparalleled access to the band over the course of their extraordinary career and has a unique archive of interviews with Gerard Way and his brother Mikey, Ray Toro and Frank Iero, as well as their friends and those closest to them, allowing him to go behind the scenes and bring their stories to life. From their New Jersey beginnings to international superstardom, from the demons they have battled to the power of their lyrics and their extraordinary connection with their fans, this is the definitive biography of the most adored rock band this century, a story of self-belief and the pursuit of dreams. UK edition: http://amzn.to/1myGFjA US edition: http://amzn.to/1ig2Lo7 |

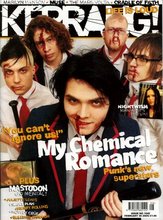

My Chemical Romance interview: how Three Cheers For Sweet Revenge exploded | Kerrang! February 2005

MY CHEMICAL Romance have always been fighting. Fighting their backgrounds. Fighting themselves and fighting for survival.

They fought their way out of New Jersey, out of lives that seemed mapped out for them since birth – of nine-to-fives, of drinking and fucking and returning home miserable about it.

They fought at school, when they didn’t know what they fighting for, as they all sat alone in classrooms and lunch halls, the strange kids, the outsiders that no-one wanted to know, who no-one gave the time of day.

They fought because they wanted to make a difference, to not be the people their peers were, to not die without having tried somehow to change someone, somewhere’s world.

They were told they would fail constantly, that they were no good, that they didn’t have the talent or the bottle to see it through.

You can see that fighting spirit when they’re on stage, you can see it when they walk into a room together and you can hear it in every note of their music. You can tell that it’s a battle that they think they might be winning. And that means everything to them because, for Gerard Way and his boys, “It’s always been about victory, glory, defeat and desire. I’ve always wanted to win…that’s all I’ve ever wanted.”

SCHOOL WAS never fun for My Chemical Romance. They were never the popular kids, never the kids who were at the centre, or even the fringes of a group. As they talk now, all of them dressed in uniforms and blood, having just trashed a school room for the purposes of the pictures alongside, there’s a slight glee in their eyes.

“I was one of the invisible people at school,” says guitarist Ray Toro. He says this without a trace of regret or pain. “I didn’t excel at anything, I wasn’t terrible at anything. After school I would go home alone and sit and play guitar or video games until the next day.”

It’s a story that rings true with every member of the band. None of them were at school together, yet all of them have this as a shared history.

Frank Iero spent high school with just three friends. He didn’t do a lot, he smoked weed, got high and, “That was about it. I knew I didn’t really want to be in school but I didn’t know what else I wanted to do.”

He was bullied. He says, “There was a lot of that”, and that he didn’t ever fit in, that he was never the sportsman or the top of the class. So he discovered punk-rock and drugs and knew that everyone thought of him as the weird kid.

If you ask any of My Chemical Romance about their school days, they tell you the same thing. Except Gerard Way. He’s perhaps the least bitter about that time, despite acknowledging that his school days were very solitary.

“I was really isolated,” he says. “But I found solace in the comic book store. That saved my life. On my first day in high school I sat all alone at lunchtime. It was the classic story – the weird kid in the army jacket, horror movie t-shirt and long, black hair.”

He found a group though, a group of metalheads who’d sit with him and talk, but Gerard never had much interest in hanging out. “I was more interested in music and being creative. People were never really mean to me, they mostly just left me alone. I think really, I just wanted to be alone.”

THOUGH THEY may not realise it, those days were vital for My Chemical Romance. The experience of being the outsiders, of always looking in at something else meant they were filled with desire to be noticed.

“We all felt like outcasts,” says Gerard Way. “That’s what brought us all together.”

“That kind of thing really fuels you,” adds Iero. “It feels good to prove people wrong. To show all the people who said you weren’t good enough and that you’d never succeed. You stay hungry because of that. You never settle and that’s a good thing.”

Iero, for one, says he was told he wouldn’t make it at least three times a day. It built up an anger in the band, one built from defiance in the face of adversity and one of revenge.

“This record <<is>> revenge for us,” says Gerard Way. “Revenge for all the people that said we would never succeed. I’ve been obsessed with revenge ever since I heard the Black Flag song ‘Revenge’. Then revenge started to mean something to this band. We thought we could get even for all the shit that’s happened to us in our lives, for being raised by good parents in a really bad area. Revenge that could mean we could break out and see the world. Most of all, revenge for all the people who never believed in us.”

It led to a strange self-confidence born out of having no-one to rely on but themselves.

“In the beginning I had this obsessive weird vive,” says Gerard Way. “I had this extreme confidence where I felt like nothing could touch us. It was as though I was always the person I was onstage. I had created that onstage character and no-one could break that…until I stopped drinking.”

THEIR HOMETOWN of New Jersey was never somewhere they loved. They spent years looking at the lives they could lead there, the lives that meant living for the Friday and Saturday nights. Of getting smashed out of your skull simply because it dulled the mundanity of the working week. It’s a large place, but small-town in mindset, everyone knows who you are and what you do there. So the band fought against it, became part of the underground punk scene – a scene that Iero describes as elitist but very caring and helpful. Then they played anywhere they could.

“We played basements, legion halls, anywhere and as often as we could,” says Iero. “I even played a hot-dog stand once. We would play anywhere because it’s all we had.”

When he’s speaking, Iero has a calm but icy exterior. There’s a real toughness about him, his words are softly spoken but hit with power. As much as Gerard Way is the frontman and the voice of the band, Iero is its heartbeat and its blood. He lives this band as his life because he has nothing else, has never wanted to do anything else and can’t see what else he might do. When he whirls around the stage, he gives his all for his band.

“I need to have given my all,” he says. “I need to know that I’ll be left on the floor and that I’m completely done after a show. I need to have nothing left. I need to feel dangerous, I need to not leave anyone standing. I want to kill the audiences.”

This pugnacious attitude saw them rise to the top of their local scene, break out and move on. Then a strange thing happened. They all realised how proud they were of Jersey. How proud they were of themselves for having broken out.

“We wanted to show people we were different,” says Gerard Way. “We went out to represent Jersey, to prove to them all that we weren’t just drunk, shithead, Mafia children. I’m very proud of where I’m from now, despite its faults.”

IT’S THAT outcast attitude that means they’ve become heroes to all the lonely people. It’s not something they asked for but they are seen as kindred spirits to all the people who occupy the corners of the rooms.

“We never set ourselves up to be marauding for the underdogs,” says Iero. “We were never trying to be superheroes or role models. But, to think that we’re looking out for the kids who don’t have anyone else feels good but we’re kids too. We don’t have all the answers.”

“That sort of thing frightens me a little,” says Gerard Way. “I guess it’s that old superhero thing – with great power comes great responsibility. We do have a power now and some people are looking at us as saviours in a way. It feels like an incredible weight on your shoulders.”

That responsibility is something that has been pressing on Gerard Way particularly. But then helping or trying to make a difference has always been the point of the band, whether it’s helping themselves or helping other people.

“At first this was group therapy for ourselves,” says Gerard. “Then it went to group therapy for a room of people. Then, with the records, it was group therapy for anyone who bought it. I hope we’re helping people but that doesn’t mean I’m going to go to people’s houses because they wrote me a suicide note. That’s not going to happen.”

Receiving suicide notes, however, is something that happens. It’s partly a symptom of being the kind of band they are, of looking like the gang that has stood up to the bullies and haters. It means people associate with them for that very reason. It also means they’re worried they’re becoming the sort of band whose fans feel they have to be fucked up to understand them.

“I think some do and it’s really heavy, really crazy,” says Gerard. “It can be threatening, a little dangerous.”

It’s something he already knows is a problem. Anyone who saw the band on their recent tour would have noticed Way’s speech on 1-800 SUICIDE, the American helpline for people thinking of taking their own lives. He never used to say it in England, partly because he doesn’t know what the UK equivalent was. Then something recently made him re-think.

“I don’t want to get too personal because I don’t want to embarrass the person involved. We always turn the houselights up during ‘Our Lady Of Sorrows’ because it’s a special song to us and we want to take a moment whether the crowd hate us, love us or are throwing beer at us. I did that on this tour and I saw someone in the crowd who was completely cut up, arms and all over. That changed everything right then. I’m worried that people might think they have to do something like that to come to one of our shows. That they have to go through that in order to fit in. I would hate to think there’s anything about this band that would encourage anyone to do that to themselves.”

It’s something that some bands could shrug off as not their problem. My Chemical Romance think it is their problem but they’re not totally sure how to deal with it. They try though because these are their kids, their fans or – as Frank Iero puts it – “our army”. It’s a lot of responsibility to shoulder.

“We’re not psycho-therapists,” says Gerard. “We’re not going to be able to do anything good for these people so we try to be mature and keep being the band we are and be there with our words and live show. We try to be honest about what’s happened to us in our lives. We’re there for people in that respect.”

That Gerard Way can associate with those urges and feelings does help. He knows what it is to hate yourself.

“I have had a lot of self hate,” he says. “The most recent example was the song ‘Helena’. It’s a really angry open letter to myself. It’s about why I wasn’t around for this woman who was so special to me, why I wasn’t there for the last year of her life. Self hate is always a big part of the lyrics. I’ve felt like that all my life. I don’t know why but I’ve always hated myself. Hopefully that self hate is growing into something else now, hopefully it’s grown into caring about myself and wanting to stay alive.”

THERE WAS a time when all that self-hate was becoming a problem for Gerard, when people were starting to wonder – himself included – whether he would stay alive. He’s talked about his problems with alcohol and drugs before, about how they very nearly sent him over the edge.

Looking at him today, he is a different person. He looks healthy – despite being splattered in fake blood and dark eye-liner. He’s also positive, something he once found it hard to be. But he’s cleaned himself up and has been sober for months now. It was a difficult process. Before he quit he would be able to hurl himself around the stage intuitively, driven by the music, drugs and the booze. Sober he found himself at a loss both onstage and off, he suddenly had time on his hands that he previously filled by being off his face.

“I felt invalid when I quit,” he says. “I felt contrived, as though I was trying to be someone fake. It was as though I’d lost the thing that made me Gerard Way. I had to concentrate on being creative, on letting that overtake the alcoholic side.”

The period shortly after he quit was, he says, one of the toughest of his life. He hit an all time low, moping about not knowing what to do with himself, wondering if all the success the band had achieved, all the adulation he’d received as a singer was down to the drunken persona he’d created for himself. Aside from his grandmother dying – the woman whose life and death inspired much of ‘Three Cheers For Sweet Revenge’ – he says, “That was the worst moment of my life. I also think losing my grandmother and the drinking were probably connected. When I quit I could see myself clearly and I wasn’t sure how much I liked it. I wasn’t confident about anything, I was just depressed. Also, when you get sober, everyone is very honest about everything you’ve done. That can be hard.”

It’s something he’s worked hard to turn around. He says he’s very tough on himself, that he has very high expectations of himself and that when he doesn’t live up to those, he gets incredibly disappointed. He used to deal with that by clamming up. Now he tries to fight them, he tries to talk to his band and his friends. It’s meant that he thinks he’s become a better person, someone with balance who finds the time to enjoy himself and to just be himself, rather than always the singer in a band.

“I would obsess over death but I’m more comfortable now. I don’t feel like I have to be the crazy, drunken, fucked up singer the whole time. I can turn it off and on now. The other guys in the band were getting so sick of me, they couldn’t believe I was like that the whole time.”

Ray Toro agrees: “It’s not a concern for us anymore, we don’t worry if he’ll slip back into it at all. When he stopped drinking and when we got our new drummer, we became much stronger. Gerard performs better, we have more fun and we don’t have to worry about what state he’s in…”

“…or if he’s stealing our stuff for drugs,” adds Iero. It’s hard to tell if he’s joking or not.

AND SO My Chemical Romance found themselves going into 2005 newly recharged. They had fired their old drummer – who, according to Ray Toro, always made them nervous before shows, “We didn’t know what might happen next onstage with him and that wasn’t good. There was a lot of shit going on and we weren’t having fun at all. They also had a sober and fired up singer once again.

On top of that, their album had been one of the critics’ albums of 2004, their shows were getting bigger and bigger and they were being touted as everyone as potential superstars. They believe it was their fighting that did it.

“We thrive on conflict, opposition…everything,” says Gerard Way. “I’ve always been like that. At first it was us versus New York City. Then it felt like the band versus America. Now it’s us versus the world.”

But, given that the world quite likes My Chemical Romance now, that their albums have been flying from the shelves, the critics have praised them unanimously, surely there’s no-one left to fight. If you’ve based your identity on being the underdogs, what happens when you’ve got the upper hand?

“It is still a fight,” says Gerard Way. “It’s funny, if we believed all the press and the reviews, we could just think we’ve got this in the bag. We feel like we’ve got the sons of bitches by the balls! That’s the best way to describe it. We’re not ready to let go either. We could sell a million records and still feel like the underdogs. I have thought about it though, you do wonder whether it will ruin the band if you’re not an underdog anymore. You can still be an underdog to yourself though.”

The heart of the band, Iero, puts it more bluntly:

“We’ve always been fighters. There will always be something to fight against. So we’ll always fight, underdogs or not. If you put a wall in front of us, we don’t look to go round it. We just bust straight through.”

Which goes a long way to summing up the confidence in My Chemical Romance at the moment. Right now, they feel as though they’ve overcome almost everything that ever held them back, that they couldn’t be stronger, better or “more like a gang,” as Iero puts it. In fact, ask Gerard Way to sum up his own band, and he sounds like a boxer before a fight.

“We’re threatening. Unstoppable. Undefeatable. Dangerous. You can’t ignore us anymore. We’re too loud.”

© Tom Bryant 2012

They fought their way out of New Jersey, out of lives that seemed mapped out for them since birth – of nine-to-fives, of drinking and fucking and returning home miserable about it.

They fought at school, when they didn’t know what they fighting for, as they all sat alone in classrooms and lunch halls, the strange kids, the outsiders that no-one wanted to know, who no-one gave the time of day.

They fought because they wanted to make a difference, to not be the people their peers were, to not die without having tried somehow to change someone, somewhere’s world.

They were told they would fail constantly, that they were no good, that they didn’t have the talent or the bottle to see it through.

You can see that fighting spirit when they’re on stage, you can see it when they walk into a room together and you can hear it in every note of their music. You can tell that it’s a battle that they think they might be winning. And that means everything to them because, for Gerard Way and his boys, “It’s always been about victory, glory, defeat and desire. I’ve always wanted to win…that’s all I’ve ever wanted.”

SCHOOL WAS never fun for My Chemical Romance. They were never the popular kids, never the kids who were at the centre, or even the fringes of a group. As they talk now, all of them dressed in uniforms and blood, having just trashed a school room for the purposes of the pictures alongside, there’s a slight glee in their eyes.

“I was one of the invisible people at school,” says guitarist Ray Toro. He says this without a trace of regret or pain. “I didn’t excel at anything, I wasn’t terrible at anything. After school I would go home alone and sit and play guitar or video games until the next day.”

It’s a story that rings true with every member of the band. None of them were at school together, yet all of them have this as a shared history.

Frank Iero spent high school with just three friends. He didn’t do a lot, he smoked weed, got high and, “That was about it. I knew I didn’t really want to be in school but I didn’t know what else I wanted to do.”

He was bullied. He says, “There was a lot of that”, and that he didn’t ever fit in, that he was never the sportsman or the top of the class. So he discovered punk-rock and drugs and knew that everyone thought of him as the weird kid.

If you ask any of My Chemical Romance about their school days, they tell you the same thing. Except Gerard Way. He’s perhaps the least bitter about that time, despite acknowledging that his school days were very solitary.

“I was really isolated,” he says. “But I found solace in the comic book store. That saved my life. On my first day in high school I sat all alone at lunchtime. It was the classic story – the weird kid in the army jacket, horror movie t-shirt and long, black hair.”

He found a group though, a group of metalheads who’d sit with him and talk, but Gerard never had much interest in hanging out. “I was more interested in music and being creative. People were never really mean to me, they mostly just left me alone. I think really, I just wanted to be alone.”

THOUGH THEY may not realise it, those days were vital for My Chemical Romance. The experience of being the outsiders, of always looking in at something else meant they were filled with desire to be noticed.

“We all felt like outcasts,” says Gerard Way. “That’s what brought us all together.”

“That kind of thing really fuels you,” adds Iero. “It feels good to prove people wrong. To show all the people who said you weren’t good enough and that you’d never succeed. You stay hungry because of that. You never settle and that’s a good thing.”

Iero, for one, says he was told he wouldn’t make it at least three times a day. It built up an anger in the band, one built from defiance in the face of adversity and one of revenge.

“This record <<is>> revenge for us,” says Gerard Way. “Revenge for all the people that said we would never succeed. I’ve been obsessed with revenge ever since I heard the Black Flag song ‘Revenge’. Then revenge started to mean something to this band. We thought we could get even for all the shit that’s happened to us in our lives, for being raised by good parents in a really bad area. Revenge that could mean we could break out and see the world. Most of all, revenge for all the people who never believed in us.”

It led to a strange self-confidence born out of having no-one to rely on but themselves.

“In the beginning I had this obsessive weird vive,” says Gerard Way. “I had this extreme confidence where I felt like nothing could touch us. It was as though I was always the person I was onstage. I had created that onstage character and no-one could break that…until I stopped drinking.”

THEIR HOMETOWN of New Jersey was never somewhere they loved. They spent years looking at the lives they could lead there, the lives that meant living for the Friday and Saturday nights. Of getting smashed out of your skull simply because it dulled the mundanity of the working week. It’s a large place, but small-town in mindset, everyone knows who you are and what you do there. So the band fought against it, became part of the underground punk scene – a scene that Iero describes as elitist but very caring and helpful. Then they played anywhere they could.

“We played basements, legion halls, anywhere and as often as we could,” says Iero. “I even played a hot-dog stand once. We would play anywhere because it’s all we had.”

When he’s speaking, Iero has a calm but icy exterior. There’s a real toughness about him, his words are softly spoken but hit with power. As much as Gerard Way is the frontman and the voice of the band, Iero is its heartbeat and its blood. He lives this band as his life because he has nothing else, has never wanted to do anything else and can’t see what else he might do. When he whirls around the stage, he gives his all for his band.

“I need to have given my all,” he says. “I need to know that I’ll be left on the floor and that I’m completely done after a show. I need to have nothing left. I need to feel dangerous, I need to not leave anyone standing. I want to kill the audiences.”

This pugnacious attitude saw them rise to the top of their local scene, break out and move on. Then a strange thing happened. They all realised how proud they were of Jersey. How proud they were of themselves for having broken out.

“We wanted to show people we were different,” says Gerard Way. “We went out to represent Jersey, to prove to them all that we weren’t just drunk, shithead, Mafia children. I’m very proud of where I’m from now, despite its faults.”

IT’S THAT outcast attitude that means they’ve become heroes to all the lonely people. It’s not something they asked for but they are seen as kindred spirits to all the people who occupy the corners of the rooms.

“We never set ourselves up to be marauding for the underdogs,” says Iero. “We were never trying to be superheroes or role models. But, to think that we’re looking out for the kids who don’t have anyone else feels good but we’re kids too. We don’t have all the answers.”

“That sort of thing frightens me a little,” says Gerard Way. “I guess it’s that old superhero thing – with great power comes great responsibility. We do have a power now and some people are looking at us as saviours in a way. It feels like an incredible weight on your shoulders.”

That responsibility is something that has been pressing on Gerard Way particularly. But then helping or trying to make a difference has always been the point of the band, whether it’s helping themselves or helping other people.

“At first this was group therapy for ourselves,” says Gerard. “Then it went to group therapy for a room of people. Then, with the records, it was group therapy for anyone who bought it. I hope we’re helping people but that doesn’t mean I’m going to go to people’s houses because they wrote me a suicide note. That’s not going to happen.”

Receiving suicide notes, however, is something that happens. It’s partly a symptom of being the kind of band they are, of looking like the gang that has stood up to the bullies and haters. It means people associate with them for that very reason. It also means they’re worried they’re becoming the sort of band whose fans feel they have to be fucked up to understand them.

“I think some do and it’s really heavy, really crazy,” says Gerard. “It can be threatening, a little dangerous.”

It’s something he already knows is a problem. Anyone who saw the band on their recent tour would have noticed Way’s speech on 1-800 SUICIDE, the American helpline for people thinking of taking their own lives. He never used to say it in England, partly because he doesn’t know what the UK equivalent was. Then something recently made him re-think.

“I don’t want to get too personal because I don’t want to embarrass the person involved. We always turn the houselights up during ‘Our Lady Of Sorrows’ because it’s a special song to us and we want to take a moment whether the crowd hate us, love us or are throwing beer at us. I did that on this tour and I saw someone in the crowd who was completely cut up, arms and all over. That changed everything right then. I’m worried that people might think they have to do something like that to come to one of our shows. That they have to go through that in order to fit in. I would hate to think there’s anything about this band that would encourage anyone to do that to themselves.”

It’s something that some bands could shrug off as not their problem. My Chemical Romance think it is their problem but they’re not totally sure how to deal with it. They try though because these are their kids, their fans or – as Frank Iero puts it – “our army”. It’s a lot of responsibility to shoulder.

“We’re not psycho-therapists,” says Gerard. “We’re not going to be able to do anything good for these people so we try to be mature and keep being the band we are and be there with our words and live show. We try to be honest about what’s happened to us in our lives. We’re there for people in that respect.”

That Gerard Way can associate with those urges and feelings does help. He knows what it is to hate yourself.

“I have had a lot of self hate,” he says. “The most recent example was the song ‘Helena’. It’s a really angry open letter to myself. It’s about why I wasn’t around for this woman who was so special to me, why I wasn’t there for the last year of her life. Self hate is always a big part of the lyrics. I’ve felt like that all my life. I don’t know why but I’ve always hated myself. Hopefully that self hate is growing into something else now, hopefully it’s grown into caring about myself and wanting to stay alive.”

THERE WAS a time when all that self-hate was becoming a problem for Gerard, when people were starting to wonder – himself included – whether he would stay alive. He’s talked about his problems with alcohol and drugs before, about how they very nearly sent him over the edge.

Looking at him today, he is a different person. He looks healthy – despite being splattered in fake blood and dark eye-liner. He’s also positive, something he once found it hard to be. But he’s cleaned himself up and has been sober for months now. It was a difficult process. Before he quit he would be able to hurl himself around the stage intuitively, driven by the music, drugs and the booze. Sober he found himself at a loss both onstage and off, he suddenly had time on his hands that he previously filled by being off his face.

“I felt invalid when I quit,” he says. “I felt contrived, as though I was trying to be someone fake. It was as though I’d lost the thing that made me Gerard Way. I had to concentrate on being creative, on letting that overtake the alcoholic side.”

The period shortly after he quit was, he says, one of the toughest of his life. He hit an all time low, moping about not knowing what to do with himself, wondering if all the success the band had achieved, all the adulation he’d received as a singer was down to the drunken persona he’d created for himself. Aside from his grandmother dying – the woman whose life and death inspired much of ‘Three Cheers For Sweet Revenge’ – he says, “That was the worst moment of my life. I also think losing my grandmother and the drinking were probably connected. When I quit I could see myself clearly and I wasn’t sure how much I liked it. I wasn’t confident about anything, I was just depressed. Also, when you get sober, everyone is very honest about everything you’ve done. That can be hard.”

It’s something he’s worked hard to turn around. He says he’s very tough on himself, that he has very high expectations of himself and that when he doesn’t live up to those, he gets incredibly disappointed. He used to deal with that by clamming up. Now he tries to fight them, he tries to talk to his band and his friends. It’s meant that he thinks he’s become a better person, someone with balance who finds the time to enjoy himself and to just be himself, rather than always the singer in a band.

“I would obsess over death but I’m more comfortable now. I don’t feel like I have to be the crazy, drunken, fucked up singer the whole time. I can turn it off and on now. The other guys in the band were getting so sick of me, they couldn’t believe I was like that the whole time.”

Ray Toro agrees: “It’s not a concern for us anymore, we don’t worry if he’ll slip back into it at all. When he stopped drinking and when we got our new drummer, we became much stronger. Gerard performs better, we have more fun and we don’t have to worry about what state he’s in…”

“…or if he’s stealing our stuff for drugs,” adds Iero. It’s hard to tell if he’s joking or not.

AND SO My Chemical Romance found themselves going into 2005 newly recharged. They had fired their old drummer – who, according to Ray Toro, always made them nervous before shows, “We didn’t know what might happen next onstage with him and that wasn’t good. There was a lot of shit going on and we weren’t having fun at all. They also had a sober and fired up singer once again.

On top of that, their album had been one of the critics’ albums of 2004, their shows were getting bigger and bigger and they were being touted as everyone as potential superstars. They believe it was their fighting that did it.

“We thrive on conflict, opposition…everything,” says Gerard Way. “I’ve always been like that. At first it was us versus New York City. Then it felt like the band versus America. Now it’s us versus the world.”

But, given that the world quite likes My Chemical Romance now, that their albums have been flying from the shelves, the critics have praised them unanimously, surely there’s no-one left to fight. If you’ve based your identity on being the underdogs, what happens when you’ve got the upper hand?

“It is still a fight,” says Gerard Way. “It’s funny, if we believed all the press and the reviews, we could just think we’ve got this in the bag. We feel like we’ve got the sons of bitches by the balls! That’s the best way to describe it. We’re not ready to let go either. We could sell a million records and still feel like the underdogs. I have thought about it though, you do wonder whether it will ruin the band if you’re not an underdog anymore. You can still be an underdog to yourself though.”

The heart of the band, Iero, puts it more bluntly:

“We’ve always been fighters. There will always be something to fight against. So we’ll always fight, underdogs or not. If you put a wall in front of us, we don’t look to go round it. We just bust straight through.”

Which goes a long way to summing up the confidence in My Chemical Romance at the moment. Right now, they feel as though they’ve overcome almost everything that ever held them back, that they couldn’t be stronger, better or “more like a gang,” as Iero puts it. In fact, ask Gerard Way to sum up his own band, and he sounds like a boxer before a fight.

“We’re threatening. Unstoppable. Undefeatable. Dangerous. You can’t ignore us anymore. We’re too loud.”

© Tom Bryant 2012