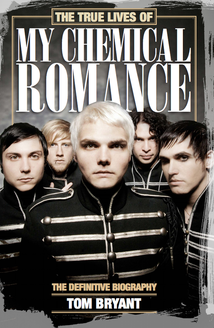

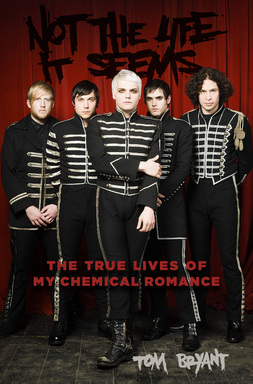

The true lives of my chemical romance: a biography

|

The definitive biography of My Chemical Romance

My Chemical Romance are the most significant band in alternative rock for the last decade, selling 5 million albums and selling out arenas worldwide until their split after twelve years together. Author Tom Bryant has been given unparalleled access to the band over the course of their extraordinary career and has a unique archive of interviews with Gerard Way and his brother Mikey, Ray Toro and Frank Iero, as well as their friends and those closest to them, allowing him to go behind the scenes and bring their stories to life. From their New Jersey beginnings to international superstardom, from the demons they have battled to the power of their lyrics and their extraordinary connection with their fans, this is the definitive biography of the most adored rock band this century, a story of self-belief and the pursuit of dreams. UK edition: http://amzn.to/1myGFjA US edition: http://amzn.to/1ig2Lo7 |

My Chemical Romance: the making of Danger Days, part two, Kerrang! October 13, 2010

This is the second of two consecutive covers published in Kerrang! To read part one of the Danger Days story, click here.

OUT IN the California desert Gerard Way was not having a crisis, exactly, but he wasn’t happy either. He had gone there, alongside his wife Lindsey and daughter Bandit, to get a little space to think. His band, My Chemical Romance, were still in the mixing stages of what they thought would be their fourth record, the all important follow-up to The Black Parade.

What they had recorded was a direct, raw and pounding punk record, one that rejected the flamboyance, pageantry and detailed ceremony of old. Instead, they had simply wanted to rock – no metaphors, no concepts, and no meanings for sensationalist journalists to misconstrue: just rock.

You could see their point. The Black Parade had made them such a phenomenon, but it had also drained them. It had made them scapegoats and ludicrously, in the eyes of some newspapers, the leaders of a suicide cult. It had become something different from what they intended; meanwhile all its achievements and everything it came to symbolise loomed large above them. And they wanted to destroy it.

What My Chemical Romance were desperate to do at the beginning of 2009 was to simply rock out, nothing more, nothing less. Gerard said he wanted to write a love letter to rock ‘n’ roll. So that’s the record that they made – bare, simple and stark – and it was very nearly the album that they released too.

“We had singles picked and people were pumped about it,” says the band’s bass player, and Gerard’s brother, Mikey Way. “We’d done some interviews and some covers and we were ready to go.”

But something wasn’t right. Ray Toro, My Chemical Romance’s guitarist, felt it, as did everyone else in the inner circle.

“The soul just wasn’t there,” he said.

“It just didn’t have the greatness,” the band’s other guitarist Frank Iero added.

The problem with what they had made, they now retrospectively realise, is that they were so concerned with what it wasn’t going to be – not The Black Parade, essentially – that they’d tried too hard to define their new music with rules.

“It was not going to be Black Parade, there would be no concept, no costumes, no exuberant layering,” says Frank. “It had to be stripped down to its barest form. I really think that the only way to create something new is to destroy what you have. Otherwise your trajectory is predictable and that’s never fun. But in doing that, I don’t think we achieved our potential. Our main problem, I think, was that we decided what the record was going to be before we actually wrote it.”

The rules they had written were dictating the songs, whereas before they had allowed themselves to be guided by the music.

“We realised that, when we were in the studio, we weren’t doing the things that we’re really great at,” says Ray. “We were trying to do something different and that meant we weren’t letting the songs be what they wanted. We had all these restrictions on everything. It wasn’t working.”

But still they struggled with it, trying to force the songs into shape in the mixing process, pushing against something that had nowhere to go. Then something happened. Gerard took some time away, spending it in the desert with his family. There the singer did some thinking. And that would change everything.

GERARD WAY speaks of his time in the desert as an epiphany. It was the realisation he had there which would lead eventually to the creation of Danger Days: True Lives Of The Fabulous Killjoys, My Chemical Romance’s eventual fourth album.

Out in the wilderness in a rented bungalow with his wife and daughter, Gerard was not simply thinking about where the My Chemical Romance record should go but also about where his band fitted in, what they should be. He wondered if they were still hungry.

“For a bunch of guys who hadn’t got into this for [the money], we had found ourselves living comfortably,” he says of what was going through his head. “We weren’t living extravagantly but it was nice to be maintaining a mortgage, especially with a baby. I wondered if we were getting too respectable.

“You’re older, you’re in your thirties and your band has established itself. It has overcome every hurdle to make great records and you’ve been celebrated for it. Next, you are slowly assimilated into modern rock culture and people begin to need 30-year-old heroes, they need respectable heroes who cut their hair. If you’re in your 30s, making your fourth album and you’ve been around for 10 years, then you notice that start to happen.”

It was a worry born from recent events. Shortly before that time he had graced several magazine covers dressed in a shirt, tie and rain mac – respectable clothes for a banker, let alone a rock singer. The band had also done some fashion shoots; they were becoming the epitome of the former hell-raisers turned upright rockers.

“I was on the cover of the NME wearing a tie and a raincoat,” he says. “I was looking at that image going, ‘Is this what I’m going to look like from now on?’ Suddenly we were getting all these offers to be on the covers of men’s magazines. We would never have got that on Black Parade or Revenge because we were so crazy looking then. At first it was flattering. I thought, ‘Oh cool, I guess that means I’m growing up.’ And then you realise that it’s the biggest trap of all, it’s the giant bear trap that’s going to stop you from running.”

He felt that what was missing was the recklessness of old, the daring, do anything craziness that had defined how bold they had previously been. It was beginning to become a worry. But then his wife stepped in.

“She told me, ‘You’re an <<artist>>. You’re not just a musician, look at what you did on Parade’,” says Gerard. “It was the first time someone had said that to me. She could see better than me how I was connecting the dots. But she said I needed to own that. She said we needed to go out and show people. That was a great compliment and a crazy thing to hear. I feel good about it; it doesn’t feel arrogant to admit it: I am an artist.”

So, with permission granted to indulge himself, the mental walls came down. He began to write lyrics to an old riff which the band had never managed to get to move in the right way. He allowed himself to go anywhere with it, to be wild imaginatively, letting a comic book he was working on about a set of characters called The Killjoys inform him. He thought about consumerism, about pop-art, about making pop into art; he thought about the world and where it was going, about the accusations that had been thrown at his band and he let rip, pouring it all into the song that would become Na Na Na.

It’s that song that now opens Danger Days, but it was also that song that opened a whole new world to My Chemical Romance.

“Anything we thought was daring on Black Parade was now old hat,” says Gerard. “We were going to go much crazier and much further than that. If people were accusing us of fucking people up and of destroying youth culture then we <<were>> going to be that dangerous. We were going to be really fucking dangerous.”

WHEN GERARD returned to Los Angeles, the band met up with their friend, the producer Rob Cavallo, who had helmed The Black Parade. The idea was to try and track one more song in an effort to tie that doomed album together. Then Gerard told them about Na Na Na.

“G said, ‘Hey, I’ve got this song’,” says Ray. “So we tried it out in the studio. For the first time in a year, you could feel us going ahead on all cylinders. The creative juices and the energy was back. As soon as Na Na Na was done, then things definitely changed. That proved what we were capable of.”

From that moment on, everything felt different. The band began to experiment again, they began to make daring decisions as to where they could go with their music. But they never quite admitted they had started recording a new album. It was perhaps that which gave them the freedom to move forward.

“That’s probably why we got this record to the point we did – because there were no rules at that point,” says Frank. “We didn’t think we <<were>> writing a new record so we didn’t ever say, ‘That’s too crazy’ or ‘We can’t put that on a record’.”

There was, though, one thing that was still a problem. It was around this time, in March of this year, that it was announced that their drummer Bob Bryar would be leaving the band. It’s not a topic they are willing to discuss in great detail, except to say this:

“There’s no way we could have done this record the way we were,” says Frank. “That’s really the only way I can put it. It breaks my heart that it had to be this way but I understand why it did. It didn’t come from out of the blue and it wasn’t anything hasty; I don’t think those things can be. In order for the band to move forward and survive, it needed to be the four of us.”

It was the only awkward point of what would become a fertile time for My Chemical Romance. With Rob Cavallo back behind the mixing desk, things began to fall into place.

“Before Na Na Na, Rob had told us what a shame it was to see a band who were just stagnant,” he said. “He was upset to the point of tears and we had never really seen someone care about the band as much us. He told us that we had to write this [new record]. From then on, there were no restrictions. There was no limit on what sort of songs we could write or what sort of sounds we could get. It was the best collaborative experience you could ever hope for.”

Cavallo was equally pleased to be with the band after their false start.

“It can be a scary thing for a band to look at a blank sheet of paper,” says the producer of the problems My Chemical Romance first faced. “I think what might have happened is that they jumped in too early. But they are such a creative and fearless band. Gerard’s mind is awesome. There are a lot of big wheels turning in there. As a producer it’s great because I can latch on to that and harness it. If you give [the band] freedom and an environment in which to work with that, then good things can happen.”

And good things were certainly happening.

AFTER NA Na Na, the songs began to flow. “Everything was so immediate because we wanted to get everything into the world as quickly as possible,” says Gerard.

First came Vampire Money, a raucous romp that closes Danger Days, but next came another breakthrough – and perhaps the boldest song My Chemical Romance have yet recorded.

Planetary (GO!) is a synth-driven dance song infused with a violent punk energy and a pounding four-to-the-floor beat. In terms of sound, it is a bolt from the blue and, as such, required the band to fully commit to it.

“Planetary (GO!) was really fucking crazy for us,” says Ray. “It was late night and Gerard heard the hook. I wanted that four-on-the-floor kick and we wanted to do a dance thing, but we wanted it to fucking shred. It was like, ‘Fuck it, who cares?’ If you do something with conviction, then it’s undeniable. I feel that we’ve been trying to write that song since the start of the band.”

“We were like, ‘Wow! We made a fucking dance song’,” says Gerard. “But it’s a dance song with a vendetta’. Everyone was playing so hard, I’d never heard anything like it.”

“It was a great night,” adds Mikey. “That was the night we realised the rule book was in cinders on the ground. We threw it away and it was like a dream. It was like being chained and then getting free – we found a whole new world that we didn’t know was there.”

The song also proved to them that they could work with keyboards and synth sounds and not only make them convincing, but make them their own. SING, the fourth track on the album followed, and it’s another song dominated by simmering electronics before a big, call-to-arms chorus. It’s perhaps telling that, bar Bulletproof Heart, Danger Days opens with Na Na Na, SING and Planetary (GO!), the three songs that paved the way for My Chemical Romance’s future.

“Those songs were all really key in showing us we could do anything we wanted to,” says Ray. “They’re kind of undeniable and that energy really carried us.”

“Those songs showed us what was going on,” says Mikey. “That’s when we decided: ‘That other record? Forget about it’.”

SOMETHING ELSE that was key was that Gerard had rediscovered his mojo. Where on the scrapped album he says he found lyric-writing “a chore”, now words were coming more freely.

His problem had been a mental one. On both The Black Parade and Three Cheers For Sweet Revenge, he had delved into himself and found it a dark and oppressive experience. One album had detailed the death of his much-loved grandmother and his own teenage issues, on the other he was dealing, metaphorically, with death itself. That his brother Mikey had suffered depression during the recording of the last album seemed only to emphasise how bleak a practice My Chemical Romance’s creative process could be.

“I think perhaps I was worried I was going to have face dark shit again in order to make great art,” he says of the difficulties he had on the abandoned album. “That’s how I’ve done it before so maybe I kept avoiding it.”

But he came to realise that he didn’t need to look so internally for his lyrics anymore. The break after The Black Parade had allowed him to do some living, to start a family and take his head out of the My Chemical Romance bubble. As Mikey says, “you have to have some experiences to be able to write”. Now, rather than simply write about himself, he had the rest of the world to turn to – and he didn’t have to wrap his thoughts in protective layers of story and characterisation as he had before.

“I could write about the shit I was too afraid to say. It was how I felt about things. I’m not really condemning anything in the world; I’m just saying my opinion. I was always hiding behind a layer of fiction. Na Na Na is the truth; everything on SING is the fucking truth. There’s no fiction to it. It wasn’t about singing about fucked up shit, it was about digging deep and working hard. And the beauty of it this time was that it was fun. This record was fun to make.”

He used some of the themes he had been working on in his Killjoys comic, turning his attention to corporate clean-ups and rules set by the powers-that-be. Where once he would have steeped this in darkness, now he has painted everything with a broad, Technicolor palette – just look at the bright album trailer the band posted on their website, or the pop-art of Na Na Na’s vibrant video for evidence. And with all this realised, Gerard dismissed all the rules of before and went feral.

“I have no control anymore – I learned to really fucking embrace that,” he says. “We’re all fucking wild. That’s what Danger Days is. It’s saying there are no rules, there’s no control. No-one’s in charge, this is pure chaos. Danger Days is a cruise missile pointed at rock ‘n’ roll. It’s a warhead. We don’t do anything but bold! And we don’t care about the aftermath at all.”

WHEN MY Chemical Romance started to the process that would eventually lead to Danger Days, things had seemed so black and white. The hangover from The Black Parade – a record so steeped, image-wise, in monochrome shades – left them with stark rules which only served to show them what they couldn’t do. When they embraced colour, they found the key – a theory that Gerard credits his friend, the comic-book artist Grant Morrison for helping him realise.

Today, as the four members of My Chemical Romance talk in tones of pure excitement about their new record, they are anything but colourless. There’s what they look like for starters. Gerard’s vivid red hair contrasts sharply with the bright yellow mask he’ll wear for photo shoots; his bandmates too, dressed in bold candy-coloured shades, couldn’t look more different. Here we are, they seem to be saying, you can’t miss us: come and have a go.

“Black is no longer dangerous,” says Gerard. “Vampires have become accepted in culture, they’re mainstream as hell. So what’s dangerous now? Colour. Colour is super dangerous. That’s the thing that’s going to get a reaction.”

But it’s colour that’s not just characterised by the clothes they wear. It’s in their smiles, it’s in their eyes, it’s in their conviction. I’ve interviewed My Chemical Romance many times since the release of Three Cheers For Sweet Revenge and rarely have they seemed so bright and happy. Today, they’re radiant.

“The future’s bulletproof,” says Gerard, thinking about this. “It’s bright as hell. It’s bold, colourful and very, very fast. We’re free, now. And we sound like a band who are free – and to me, that is the sound of pure rock ‘n’ roll.”

And he’s right.

© Tom Bryant 2010

OUT IN the California desert Gerard Way was not having a crisis, exactly, but he wasn’t happy either. He had gone there, alongside his wife Lindsey and daughter Bandit, to get a little space to think. His band, My Chemical Romance, were still in the mixing stages of what they thought would be their fourth record, the all important follow-up to The Black Parade.

What they had recorded was a direct, raw and pounding punk record, one that rejected the flamboyance, pageantry and detailed ceremony of old. Instead, they had simply wanted to rock – no metaphors, no concepts, and no meanings for sensationalist journalists to misconstrue: just rock.

You could see their point. The Black Parade had made them such a phenomenon, but it had also drained them. It had made them scapegoats and ludicrously, in the eyes of some newspapers, the leaders of a suicide cult. It had become something different from what they intended; meanwhile all its achievements and everything it came to symbolise loomed large above them. And they wanted to destroy it.

What My Chemical Romance were desperate to do at the beginning of 2009 was to simply rock out, nothing more, nothing less. Gerard said he wanted to write a love letter to rock ‘n’ roll. So that’s the record that they made – bare, simple and stark – and it was very nearly the album that they released too.

“We had singles picked and people were pumped about it,” says the band’s bass player, and Gerard’s brother, Mikey Way. “We’d done some interviews and some covers and we were ready to go.”

But something wasn’t right. Ray Toro, My Chemical Romance’s guitarist, felt it, as did everyone else in the inner circle.

“The soul just wasn’t there,” he said.

“It just didn’t have the greatness,” the band’s other guitarist Frank Iero added.

The problem with what they had made, they now retrospectively realise, is that they were so concerned with what it wasn’t going to be – not The Black Parade, essentially – that they’d tried too hard to define their new music with rules.

“It was not going to be Black Parade, there would be no concept, no costumes, no exuberant layering,” says Frank. “It had to be stripped down to its barest form. I really think that the only way to create something new is to destroy what you have. Otherwise your trajectory is predictable and that’s never fun. But in doing that, I don’t think we achieved our potential. Our main problem, I think, was that we decided what the record was going to be before we actually wrote it.”

The rules they had written were dictating the songs, whereas before they had allowed themselves to be guided by the music.

“We realised that, when we were in the studio, we weren’t doing the things that we’re really great at,” says Ray. “We were trying to do something different and that meant we weren’t letting the songs be what they wanted. We had all these restrictions on everything. It wasn’t working.”

But still they struggled with it, trying to force the songs into shape in the mixing process, pushing against something that had nowhere to go. Then something happened. Gerard took some time away, spending it in the desert with his family. There the singer did some thinking. And that would change everything.

GERARD WAY speaks of his time in the desert as an epiphany. It was the realisation he had there which would lead eventually to the creation of Danger Days: True Lives Of The Fabulous Killjoys, My Chemical Romance’s eventual fourth album.

Out in the wilderness in a rented bungalow with his wife and daughter, Gerard was not simply thinking about where the My Chemical Romance record should go but also about where his band fitted in, what they should be. He wondered if they were still hungry.

“For a bunch of guys who hadn’t got into this for [the money], we had found ourselves living comfortably,” he says of what was going through his head. “We weren’t living extravagantly but it was nice to be maintaining a mortgage, especially with a baby. I wondered if we were getting too respectable.

“You’re older, you’re in your thirties and your band has established itself. It has overcome every hurdle to make great records and you’ve been celebrated for it. Next, you are slowly assimilated into modern rock culture and people begin to need 30-year-old heroes, they need respectable heroes who cut their hair. If you’re in your 30s, making your fourth album and you’ve been around for 10 years, then you notice that start to happen.”

It was a worry born from recent events. Shortly before that time he had graced several magazine covers dressed in a shirt, tie and rain mac – respectable clothes for a banker, let alone a rock singer. The band had also done some fashion shoots; they were becoming the epitome of the former hell-raisers turned upright rockers.

“I was on the cover of the NME wearing a tie and a raincoat,” he says. “I was looking at that image going, ‘Is this what I’m going to look like from now on?’ Suddenly we were getting all these offers to be on the covers of men’s magazines. We would never have got that on Black Parade or Revenge because we were so crazy looking then. At first it was flattering. I thought, ‘Oh cool, I guess that means I’m growing up.’ And then you realise that it’s the biggest trap of all, it’s the giant bear trap that’s going to stop you from running.”

He felt that what was missing was the recklessness of old, the daring, do anything craziness that had defined how bold they had previously been. It was beginning to become a worry. But then his wife stepped in.

“She told me, ‘You’re an <<artist>>. You’re not just a musician, look at what you did on Parade’,” says Gerard. “It was the first time someone had said that to me. She could see better than me how I was connecting the dots. But she said I needed to own that. She said we needed to go out and show people. That was a great compliment and a crazy thing to hear. I feel good about it; it doesn’t feel arrogant to admit it: I am an artist.”

So, with permission granted to indulge himself, the mental walls came down. He began to write lyrics to an old riff which the band had never managed to get to move in the right way. He allowed himself to go anywhere with it, to be wild imaginatively, letting a comic book he was working on about a set of characters called The Killjoys inform him. He thought about consumerism, about pop-art, about making pop into art; he thought about the world and where it was going, about the accusations that had been thrown at his band and he let rip, pouring it all into the song that would become Na Na Na.

It’s that song that now opens Danger Days, but it was also that song that opened a whole new world to My Chemical Romance.

“Anything we thought was daring on Black Parade was now old hat,” says Gerard. “We were going to go much crazier and much further than that. If people were accusing us of fucking people up and of destroying youth culture then we <<were>> going to be that dangerous. We were going to be really fucking dangerous.”

WHEN GERARD returned to Los Angeles, the band met up with their friend, the producer Rob Cavallo, who had helmed The Black Parade. The idea was to try and track one more song in an effort to tie that doomed album together. Then Gerard told them about Na Na Na.

“G said, ‘Hey, I’ve got this song’,” says Ray. “So we tried it out in the studio. For the first time in a year, you could feel us going ahead on all cylinders. The creative juices and the energy was back. As soon as Na Na Na was done, then things definitely changed. That proved what we were capable of.”

From that moment on, everything felt different. The band began to experiment again, they began to make daring decisions as to where they could go with their music. But they never quite admitted they had started recording a new album. It was perhaps that which gave them the freedom to move forward.

“That’s probably why we got this record to the point we did – because there were no rules at that point,” says Frank. “We didn’t think we <<were>> writing a new record so we didn’t ever say, ‘That’s too crazy’ or ‘We can’t put that on a record’.”

There was, though, one thing that was still a problem. It was around this time, in March of this year, that it was announced that their drummer Bob Bryar would be leaving the band. It’s not a topic they are willing to discuss in great detail, except to say this:

“There’s no way we could have done this record the way we were,” says Frank. “That’s really the only way I can put it. It breaks my heart that it had to be this way but I understand why it did. It didn’t come from out of the blue and it wasn’t anything hasty; I don’t think those things can be. In order for the band to move forward and survive, it needed to be the four of us.”

It was the only awkward point of what would become a fertile time for My Chemical Romance. With Rob Cavallo back behind the mixing desk, things began to fall into place.

“Before Na Na Na, Rob had told us what a shame it was to see a band who were just stagnant,” he said. “He was upset to the point of tears and we had never really seen someone care about the band as much us. He told us that we had to write this [new record]. From then on, there were no restrictions. There was no limit on what sort of songs we could write or what sort of sounds we could get. It was the best collaborative experience you could ever hope for.”

Cavallo was equally pleased to be with the band after their false start.

“It can be a scary thing for a band to look at a blank sheet of paper,” says the producer of the problems My Chemical Romance first faced. “I think what might have happened is that they jumped in too early. But they are such a creative and fearless band. Gerard’s mind is awesome. There are a lot of big wheels turning in there. As a producer it’s great because I can latch on to that and harness it. If you give [the band] freedom and an environment in which to work with that, then good things can happen.”

And good things were certainly happening.

AFTER NA Na Na, the songs began to flow. “Everything was so immediate because we wanted to get everything into the world as quickly as possible,” says Gerard.

First came Vampire Money, a raucous romp that closes Danger Days, but next came another breakthrough – and perhaps the boldest song My Chemical Romance have yet recorded.

Planetary (GO!) is a synth-driven dance song infused with a violent punk energy and a pounding four-to-the-floor beat. In terms of sound, it is a bolt from the blue and, as such, required the band to fully commit to it.

“Planetary (GO!) was really fucking crazy for us,” says Ray. “It was late night and Gerard heard the hook. I wanted that four-on-the-floor kick and we wanted to do a dance thing, but we wanted it to fucking shred. It was like, ‘Fuck it, who cares?’ If you do something with conviction, then it’s undeniable. I feel that we’ve been trying to write that song since the start of the band.”

“We were like, ‘Wow! We made a fucking dance song’,” says Gerard. “But it’s a dance song with a vendetta’. Everyone was playing so hard, I’d never heard anything like it.”

“It was a great night,” adds Mikey. “That was the night we realised the rule book was in cinders on the ground. We threw it away and it was like a dream. It was like being chained and then getting free – we found a whole new world that we didn’t know was there.”

The song also proved to them that they could work with keyboards and synth sounds and not only make them convincing, but make them their own. SING, the fourth track on the album followed, and it’s another song dominated by simmering electronics before a big, call-to-arms chorus. It’s perhaps telling that, bar Bulletproof Heart, Danger Days opens with Na Na Na, SING and Planetary (GO!), the three songs that paved the way for My Chemical Romance’s future.

“Those songs were all really key in showing us we could do anything we wanted to,” says Ray. “They’re kind of undeniable and that energy really carried us.”

“Those songs showed us what was going on,” says Mikey. “That’s when we decided: ‘That other record? Forget about it’.”

SOMETHING ELSE that was key was that Gerard had rediscovered his mojo. Where on the scrapped album he says he found lyric-writing “a chore”, now words were coming more freely.

His problem had been a mental one. On both The Black Parade and Three Cheers For Sweet Revenge, he had delved into himself and found it a dark and oppressive experience. One album had detailed the death of his much-loved grandmother and his own teenage issues, on the other he was dealing, metaphorically, with death itself. That his brother Mikey had suffered depression during the recording of the last album seemed only to emphasise how bleak a practice My Chemical Romance’s creative process could be.

“I think perhaps I was worried I was going to have face dark shit again in order to make great art,” he says of the difficulties he had on the abandoned album. “That’s how I’ve done it before so maybe I kept avoiding it.”

But he came to realise that he didn’t need to look so internally for his lyrics anymore. The break after The Black Parade had allowed him to do some living, to start a family and take his head out of the My Chemical Romance bubble. As Mikey says, “you have to have some experiences to be able to write”. Now, rather than simply write about himself, he had the rest of the world to turn to – and he didn’t have to wrap his thoughts in protective layers of story and characterisation as he had before.

“I could write about the shit I was too afraid to say. It was how I felt about things. I’m not really condemning anything in the world; I’m just saying my opinion. I was always hiding behind a layer of fiction. Na Na Na is the truth; everything on SING is the fucking truth. There’s no fiction to it. It wasn’t about singing about fucked up shit, it was about digging deep and working hard. And the beauty of it this time was that it was fun. This record was fun to make.”

He used some of the themes he had been working on in his Killjoys comic, turning his attention to corporate clean-ups and rules set by the powers-that-be. Where once he would have steeped this in darkness, now he has painted everything with a broad, Technicolor palette – just look at the bright album trailer the band posted on their website, or the pop-art of Na Na Na’s vibrant video for evidence. And with all this realised, Gerard dismissed all the rules of before and went feral.

“I have no control anymore – I learned to really fucking embrace that,” he says. “We’re all fucking wild. That’s what Danger Days is. It’s saying there are no rules, there’s no control. No-one’s in charge, this is pure chaos. Danger Days is a cruise missile pointed at rock ‘n’ roll. It’s a warhead. We don’t do anything but bold! And we don’t care about the aftermath at all.”

WHEN MY Chemical Romance started to the process that would eventually lead to Danger Days, things had seemed so black and white. The hangover from The Black Parade – a record so steeped, image-wise, in monochrome shades – left them with stark rules which only served to show them what they couldn’t do. When they embraced colour, they found the key – a theory that Gerard credits his friend, the comic-book artist Grant Morrison for helping him realise.

Today, as the four members of My Chemical Romance talk in tones of pure excitement about their new record, they are anything but colourless. There’s what they look like for starters. Gerard’s vivid red hair contrasts sharply with the bright yellow mask he’ll wear for photo shoots; his bandmates too, dressed in bold candy-coloured shades, couldn’t look more different. Here we are, they seem to be saying, you can’t miss us: come and have a go.

“Black is no longer dangerous,” says Gerard. “Vampires have become accepted in culture, they’re mainstream as hell. So what’s dangerous now? Colour. Colour is super dangerous. That’s the thing that’s going to get a reaction.”

But it’s colour that’s not just characterised by the clothes they wear. It’s in their smiles, it’s in their eyes, it’s in their conviction. I’ve interviewed My Chemical Romance many times since the release of Three Cheers For Sweet Revenge and rarely have they seemed so bright and happy. Today, they’re radiant.

“The future’s bulletproof,” says Gerard, thinking about this. “It’s bright as hell. It’s bold, colourful and very, very fast. We’re free, now. And we sound like a band who are free – and to me, that is the sound of pure rock ‘n’ roll.”

And he’s right.

© Tom Bryant 2010